Rebuilding Community on the (Fujo)Web

The story of how I got here, and how we (might) get out of it

Table of Contents

This was originally a talk given at CitrusCon.

The Story So Far

Hello and welcome to Rebuilding Community on the (fujo)Web1! My name is Ms Boba and I’m here representing FujoCoded LLC, a very young company with (as you’ll see) a much longer history.

Our work focuses on empowering fujin, BL fans, and all their friends and supporters to reshape the internet into something that’s, well, better than what we have today.

So, something about me. I’ve been here on the web since the very early 2000s, when I was gifted my first computer and immediately fell in love with the internet. I was a neuroatypical kid with a lot going on in her life, and had a hard time fitting in with my peers. Then I joined a Gensoumaden Saiyuki2 community on–blast from the past–Yahoo groups, and suddenly had a space to explore my queerness and find people I truly belonged with3. Since then, I’ve been on the internet a lot. I met my long-time partner here, my best friend, and almost everyone I love and cherish.

So, as you can see, I owe a great deal to the fandom web in general, but I also owe it my career. I learned to make websites and to program to express my love for my favorite series, and when I turned out to be pretty good at it, I got to move from Europe to Silicon Valley and start working for a big internet company. At the time, I was very excited cause I felt I had the chance to give back to a place that had meant so much to me.4

Like many fannish folks, I was also a prolific Tumblr user in 2013, around when the Avengers fandom got really big5. Once again, I owe a lot to that place. I joined Tumblr during a pretty hard time in my life, and there I found friends and knowledge that helped me grow and regain my footing.

Then the place started changing.

Around 2016 many of us were concerned with a cultural shift we were seeing on the fandom internet. I still deeply loved the place, but there was a growing let’s-call-it-“increasingly mean” undercurrent.

But the real wake up call was Tumblr banning porn. Suddenly I truly saw how much the web was deteriorating and realized that if things continued going in that direction, it would just keep getting worse and worse.

The (spite-fueled) Call to Adventure

I know many people felt the same back then, but I was in a unique place to try and do something about it. I was still working in a big internet company, so I could access people who had actual power to influence this trajectory. At the time, I was just a senior software engineer with no clue about anything business-related and, frankly, zero faith in my ability to ever understand any of it. But I was on a mission, and so I got to work.

Trying to “make change from the inside” was an eye-opening experience, to say the least. One of my many “villain-origin moments” was having an executive tell me with a straight face that harassment was not a big problem on the social internet6. It was at that point that I realized how wide the disconnect was between those at the helm of these really big web giants and us who actually spent our time on the internet.7

I also got a front-row seat to some of the dynamics that cause things like “enshittification” and how pressure from big investors influences the evolution of tech platforms. I can’t say I loved any of it. Even as I made some headway, I was forced to realize that no matter how good I was, or how well-intentioned, any progress would be short-lived and double-edged. Soon, I saw that the world I had joined because I loved the internet so much was the very force that was corrupting it. This however, led to a realization…

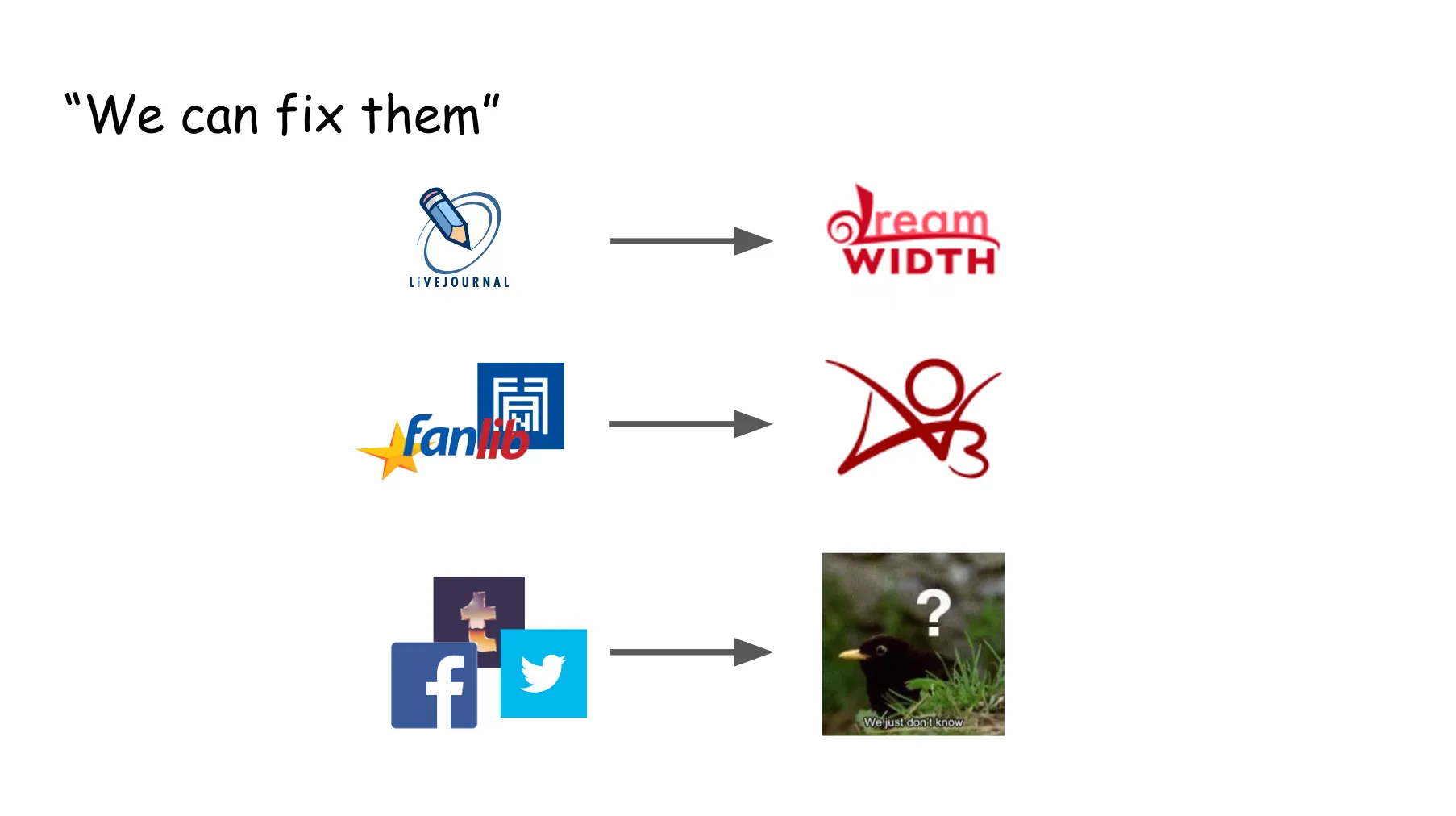

When you’re deeply embedded within a system, like I was, you can easily believe solutions can only be found within it. But I didn’t really need permission from a company or an “institutional investor” to go work on this problem. And historically we did have examples of fandom–specifically fujin-adjacent fandom!–bootstrapping ambitious, seemingly-impossible projects on the web. From the fall of LiveJournal, we got Dreamwidth. From the mass deletions of fanfictions, we got the OTW and AO3… There’s a lot of nuance to what we call “the power of fandom”, but regardless of what you think of it there exists precedent for us leading change on the web. Now, obviously, the internet today is more complex than it was when those platforms were started, and, well, fandom isn’t exactly the most tight-knit group right now. Could we as fans still come together to change the internet back to a place of authentic connection? And could we do that without losing all the positive changes of the last two decades, and make it better than it ever was?

At the time, I did not feel ready to attempt and pull people together for anything like this. But as I looked at my technical qualifications, what I had learned about how businesses and products work, and how much I cared about this problem, I had to ask myself: if I don’t do this, who will? …and so I decided to give it a try! Take it as an adventure, keep my expectations in check, go in with a growth mindset, and explore the wild world of making change on the fandom web.

What is Wrong with You the Internet?

So, step 1: an ambitious mission cannot have an ambiguous goal! Now, when you ask around, the overwhelming majority of us agrees: something about the online world is broken. But what is broken exactly? Or better said, among all the many things that are broken, what should we work on fixing?

If we think about the many ways the internet has changed, there is one I believe is waved away too early when discussing what makes the web feel so different. And that is simply the sheer number of people on it today. The internet of 2024 is 11 times larger than what it was in 2001, and more than twice as big than it was in 2013. A large size is not conducive to a feeling of intimacy and safety. Not only that, but the types of people who spend a lot of their time on the internet today, are very different than they were “before doing so was cool”.

Our online social spaces are not made for us to feel nurtured and connected when surrounded by so many people, especially when those people have so many different ways to see the world, so many different ways to do fandom, and so many different ways to conceptualize what is right and what is wrong. Research is clear on this: we’re more connected to each other than ever, especially online, but we’re also in an epidemic of loneliness. And loneliness sucks. It makes us depressed, angry, disengaged… it makes us feel like no one out there understands or cares for us. And to me that is the exactly the opposite of what the internet is supposed to be about. So what is the opposite of loneliness?

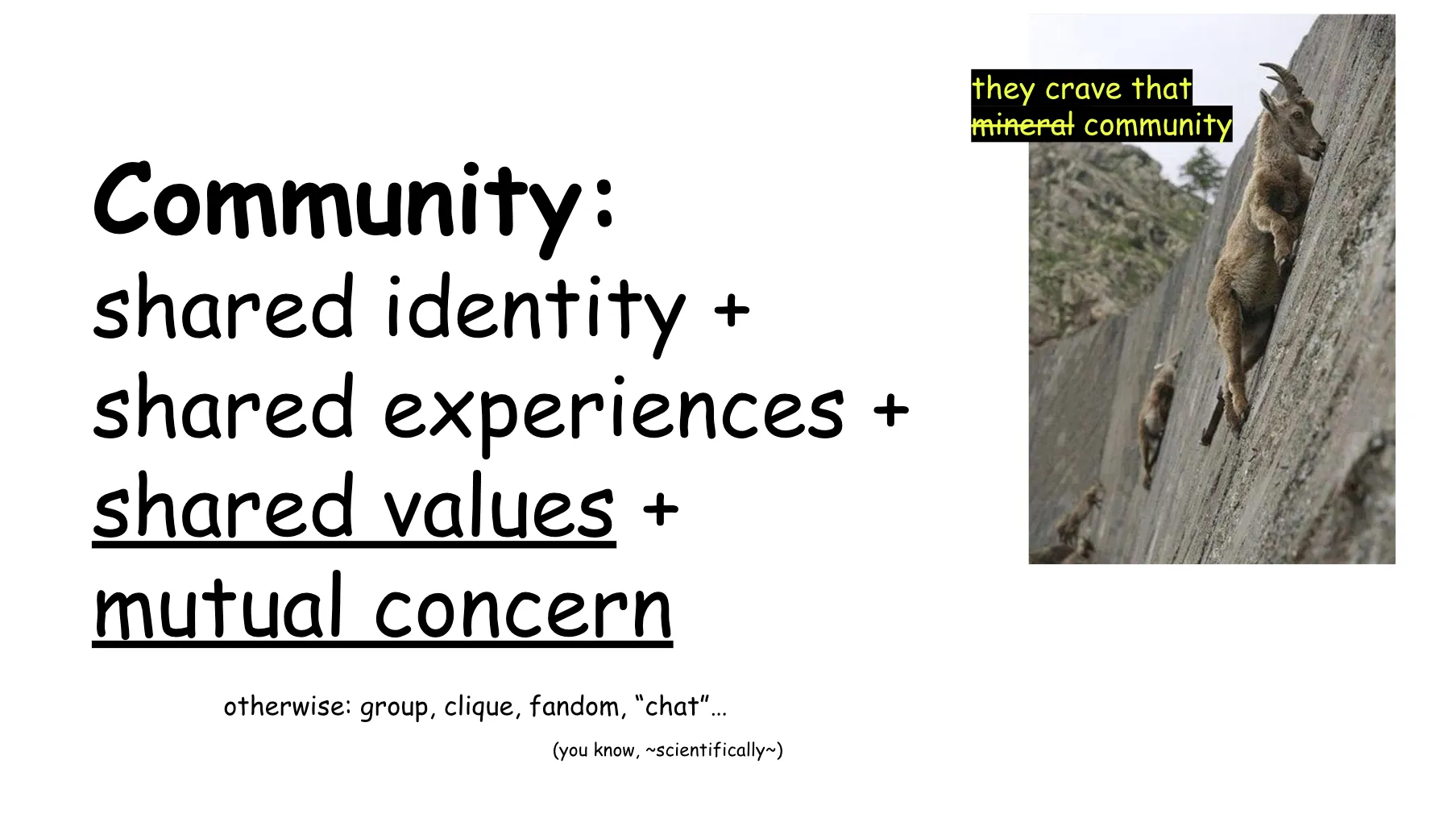

That would be community! Community is what happens when we have enough people with authentic, inter-connected relationships that are nurtured over a certain amount of time. When you think about fans of your favorite piece of media on a place like Twitter, you may think of them as a fandom, but they’re most likely not a community. That’s because they may share an identity as “fans of something”, and experiences such as “tuning in each week to see what the OTP is up to”, but unless they’re a small and tight-knit group they’re unlikely to share values and to care deeply about one another.

When you think about it in these terms, the incredible growth of Discord among fannish folks and beyond makes a lot of sense. When you can create closed, thematic spaces with (hopefully) strong moderation or at least a good invite policy, people can form authentic connections based not only on shared interests, but on shared values; this helps build mutual care and concern, and over time creates (sometimes) a real community. Now, I’m not going to go into all the reasons why the answer here isn’t just “Discord exists, problem solved”. Among other things, Discord is a platform backed by large investments, and unless they can miracle out enough money to satisfy those investors enshittification will eventually come for them too. That’s just how big tech is nowadays.

So for me the problem statement became: is it possible to build software for community on the web that knows what its ethical principles are, treats those who build it with fairness, and centers the needs of its users that are not businesses?

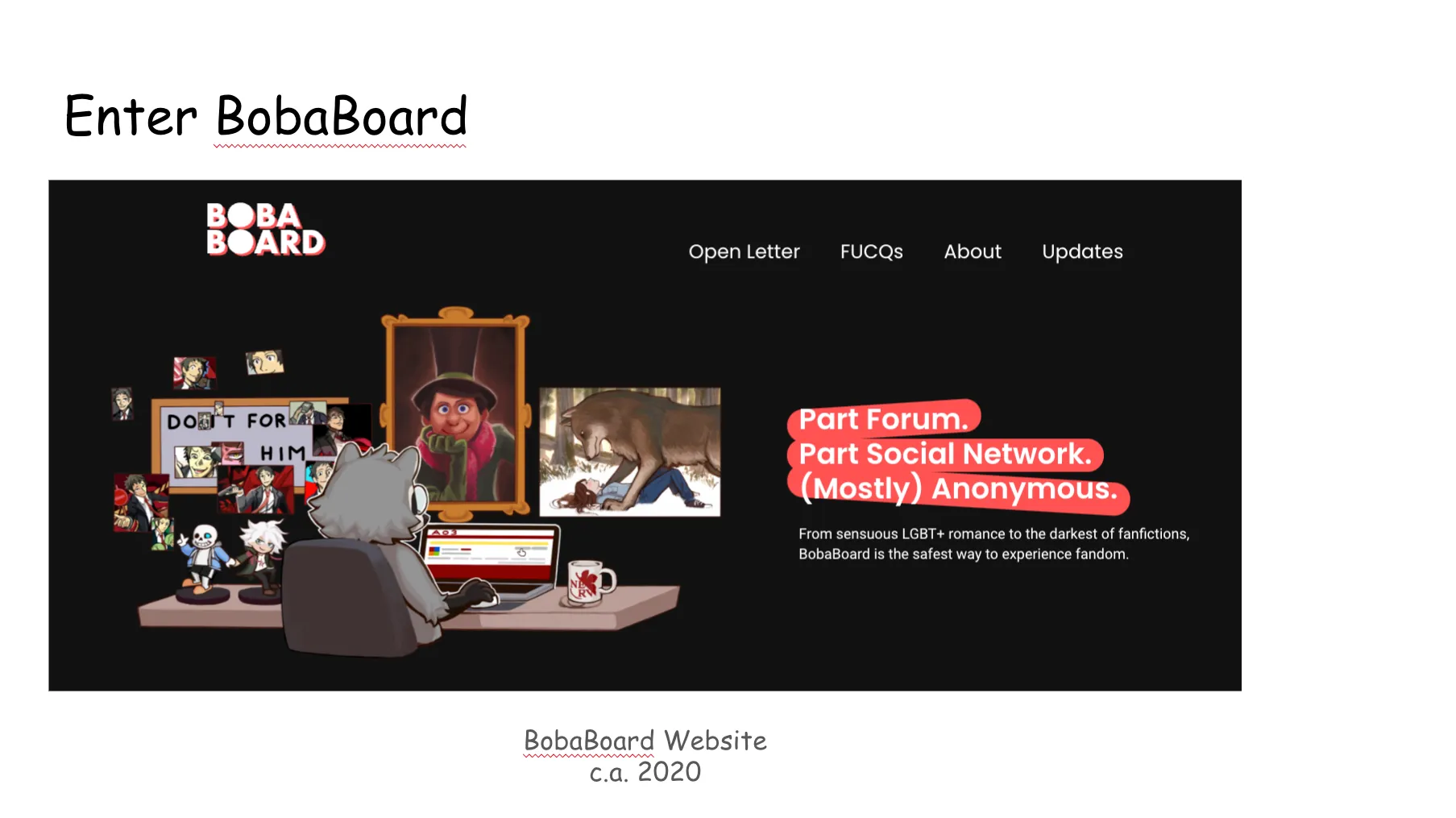

To try and answer this I quickly built a proof of concept for BobaBoard, a software to create forum-like communities modernized for current fandom. Along with upgrading some familiar features, it included some additional fun gimmicks on top, mostly related to making it possible for users to hold an identity only within the boundaries of a single thread without losing the ability to moderate. As you can see from the website, the initial branding was built to target fujin who shared my cursed sense of humor, and thus at least part of my values. I launched the first BobaBoard community right after the pandemic started, and it proved popular enough among early users that I decided to try and make it possible for others to start communities like the one we were running. As you can imagine a lot has happened since.

Not mincing words: trying to bootstrap a project like BobaBoard beyond proof of concept was a hard journey. When I connected with fandom folks who had been around the “new platform for fandom” block a few times, I was repeatedly commended for being the rare person approaching it with realism. And yet, it was still orders of magnitude more complicated than I thought it would be. Above all, something unexpected kept happening over and over: me and my collaborators would find ourselves grappling with a hard problem (usually an organizational one), but when I tried connecting with other project leads to learn how to fix it I’d find they had been struggling with the very same one, often for a long time. Even worse (or better?), sometimes it turned out we were doing a great job compared to the average, and yet the job we were doing was anything but good enough.

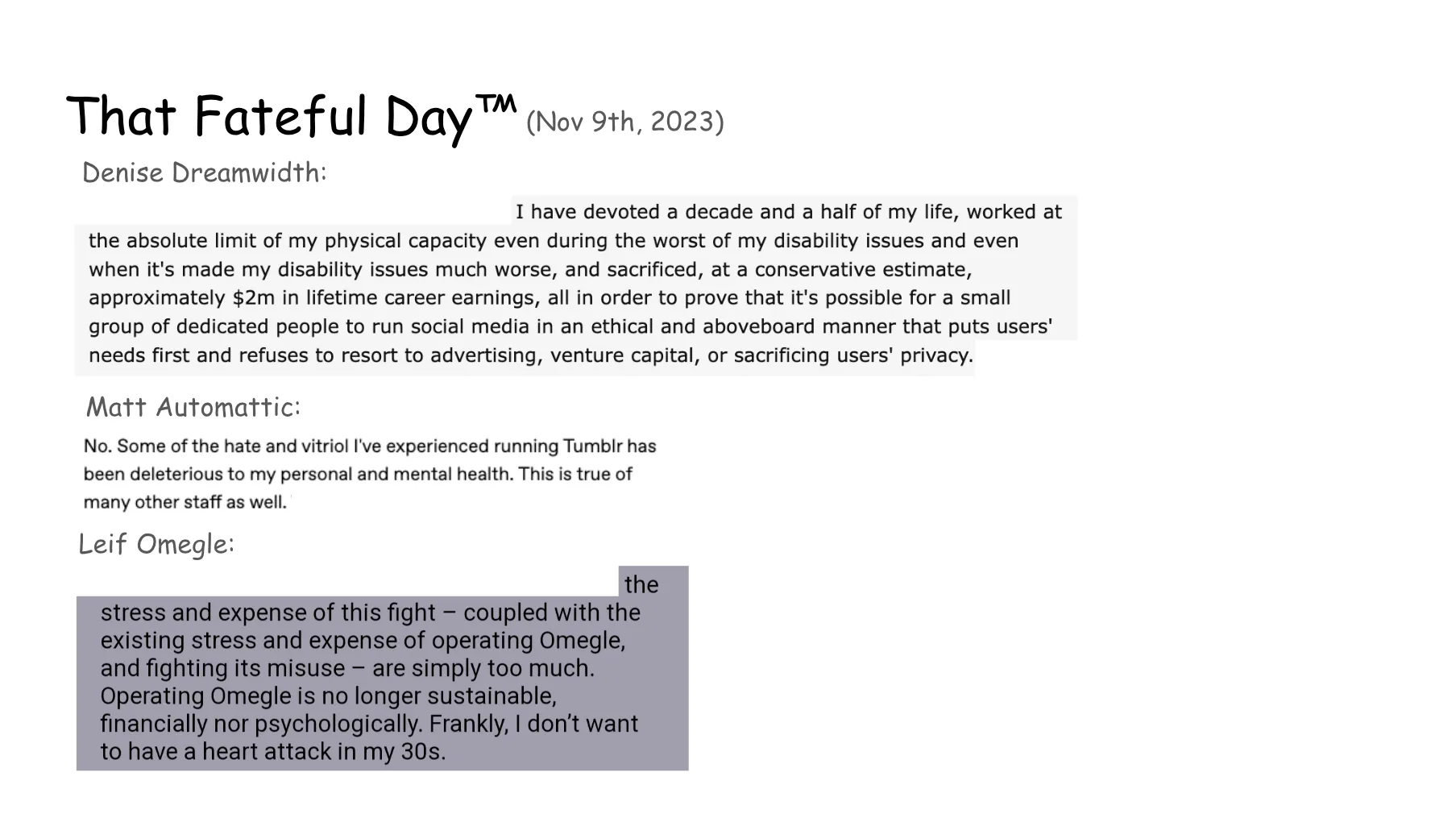

This all came to a head in November of last year. The BobaBoard team had been going through a period of intense frustration. With a team made primarily of volunteers we kept encountering false starts and stops, spending resources training newcomers just to have their lives explode in their faces and having to go back to square one. But more importantly, we were surrounded by negativity towards small platform builders, and at the same time frustrated by the overwhelming amount of responsibility placed on what is a small set of people, without what we felt was a corresponding level of support from those who directly benefited from our work. Once again I thought I must have been doing something wrong. Then on Nov 9th, 2023, three different project runners published three different posts on the same day talking about the unsustainable mental and physical toll that their projects had placed on them.

These were Denise Dreamwidth, Matt Automattic and Leif Omegle. Now, I’ll drink a glass of water and leave you a minute to read them. But before I do, I just want to say: I know some of you will balk at the inclusion of our newest Tumblr daddy. But please consider those who run projects without that amount of capital experience similar dynamics with way less layers of indirection, and way less money to have others come take care of issues on our behalf. — BREAK — Since then, I witnessed many other project leads and contributors express similar feelings. More independent projects, like retrospring recently, have been forced to close shop. Even in the larger world of open source software, maintainer burnout has been a bigger and bigger issue, with almost 60% of maintainers having considered quitting (or altogether just quitting) their own projects. When issues like these come up, people run to find explanations that focus on how the projects are run: “if only their TOS had been good! Didn’t they know better?”, “haven’t they thought about converting to a non-profit?”, “maybe if they hadn’t been rude that one time, then I’d have supported them”, or the evergreen “well, if they just added this one feature”…

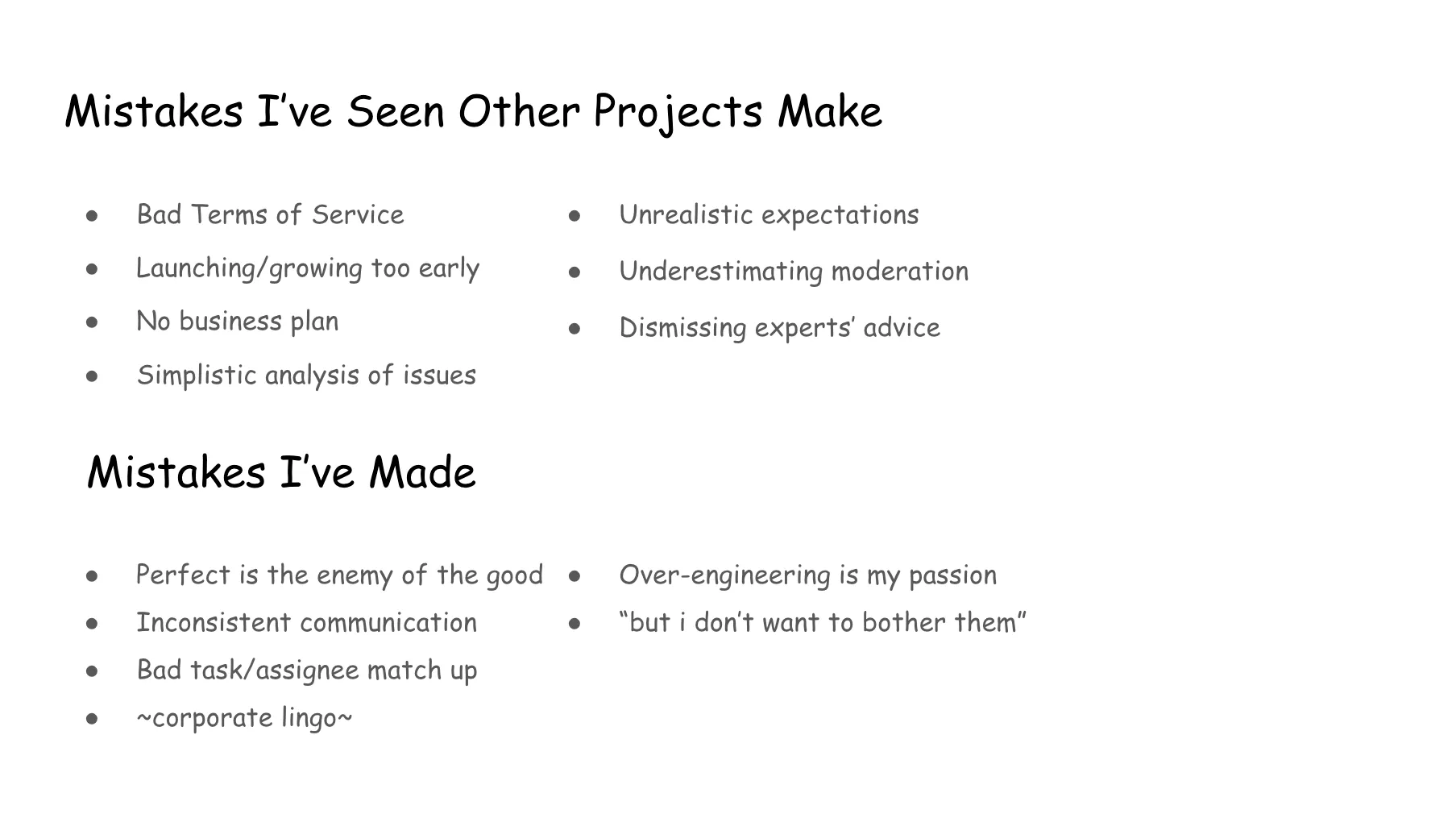

This is, of course, an understandable impulse, and not one without basis. I am personally, painfully aware that any project lead wishes they had handled something differently. And I’ve been very frustrated at avoidable mistakes I’ve seen other projects make. So here, before we move forward, I want to emphasize I don’t mean to dismiss the share of the blame on the shoulders of project runners. But over-indexing on these mistakes means missing the ever-increasing structural issues that make it harder and harder for indie projects that benefit the web to be born and to continue to exist.

Building and maintaining quality software is more and more expensive, with most non-business users unwilling or unable to pay recurring fees; the hostility in online spaces keeps escalating, and continues causing pain and frustration to already overstretched project contributors; social and economic instability makes it harder to bear the physical, emotional and financial toll of these projects; and last but not least important, many bleeding heart believers who even remember what the independent web was like are getting older, more tired, and sometimes outright passing away. With how dire things are right now, it’s hard to ask people to step in to fix the issues that plague the social web. After all, what reward is there to reap? If anyone competent enough to succeed was seeking money, they’d have an infinitely easier time and much more likelihood of success with other types of software ventures; if anyone was seeking glory, what they’ll find themselves facing as their project gains visibility is an increasingly uncharitable and for some of us outright dangerous internet.

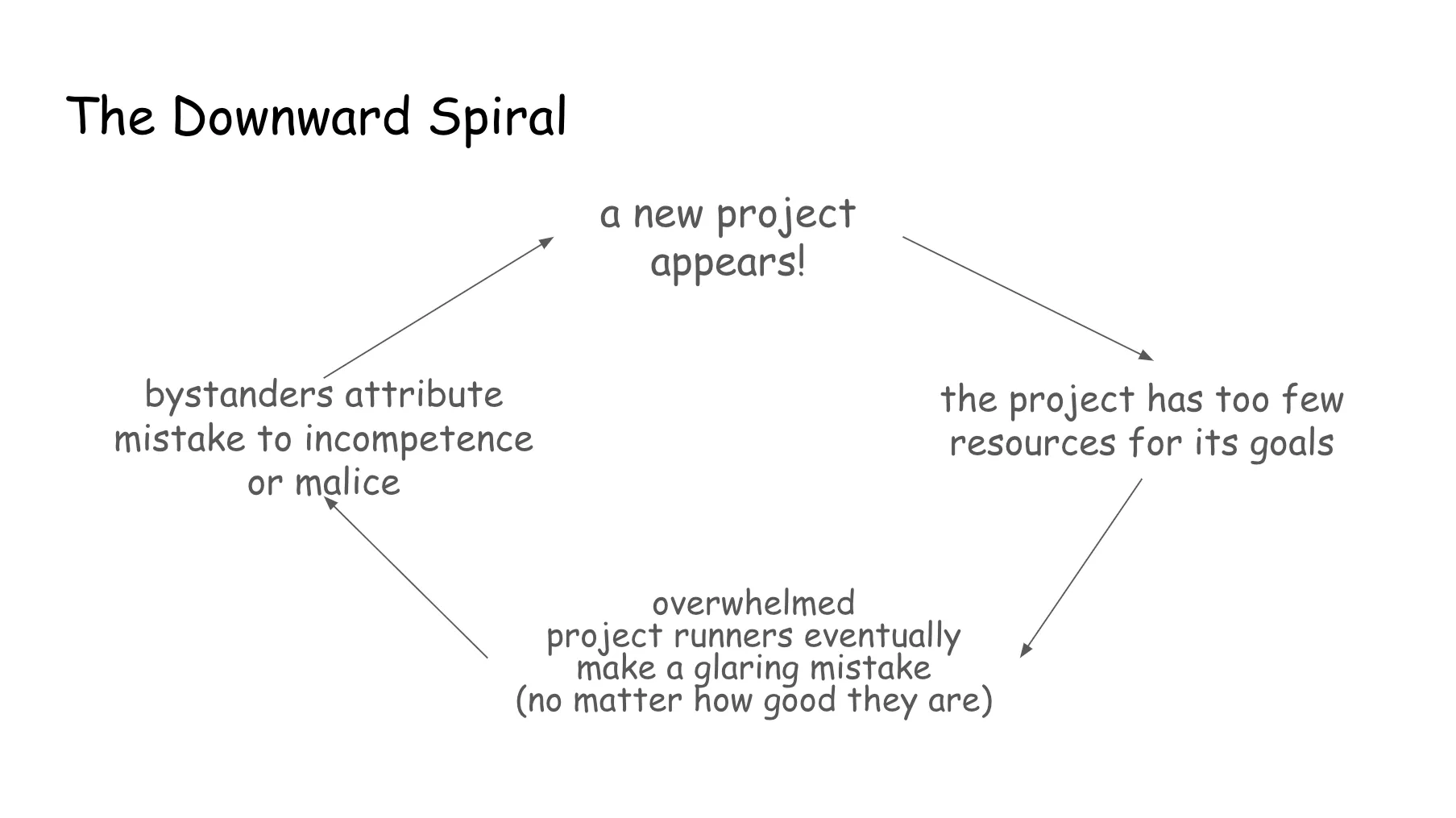

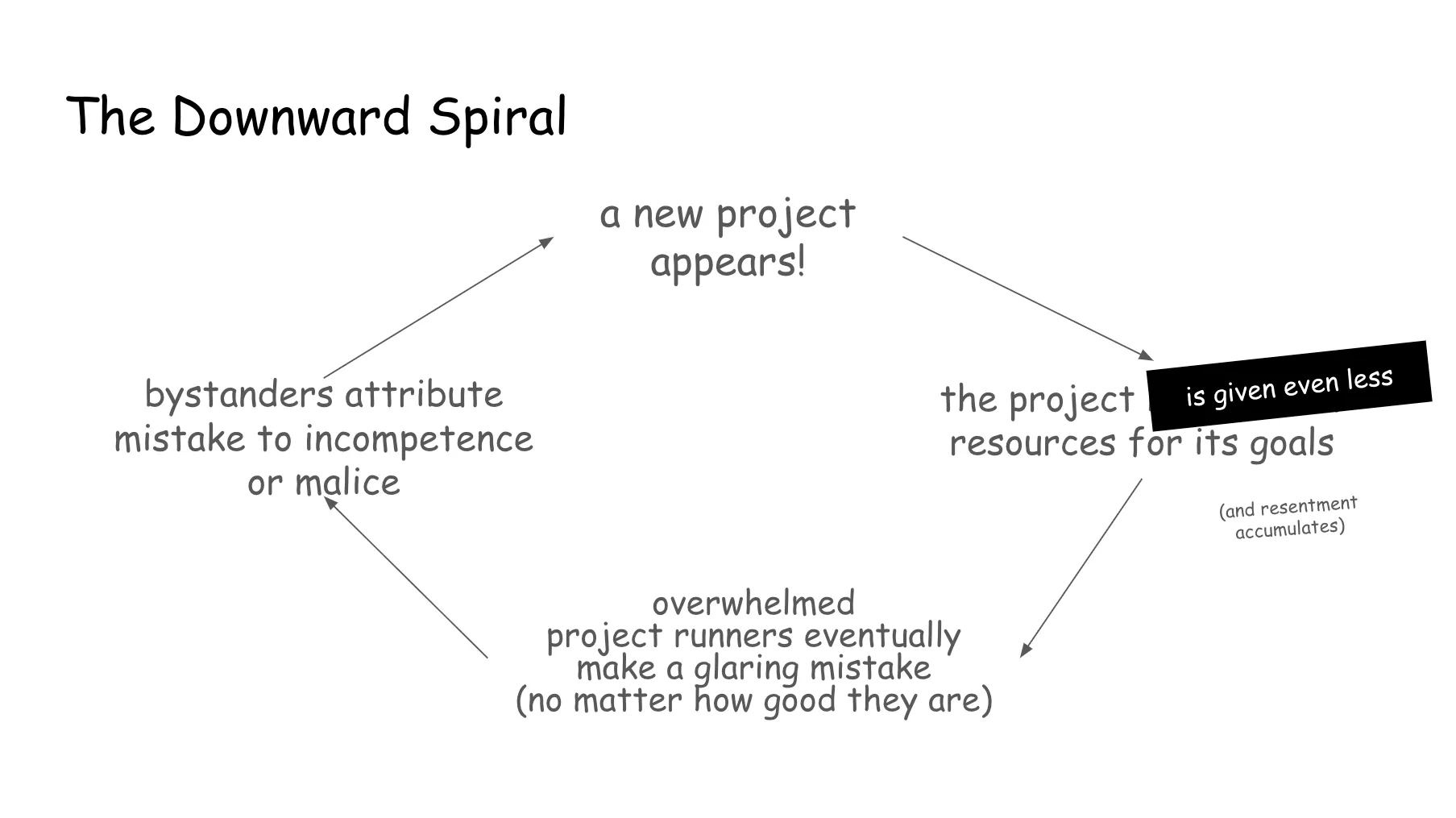

The things is, we’re currently in a downward spiral. Since large corporations keep disregarding the needs of their users and underpaying their workers, indie projects often feel that they, untouched by corporate greed and capitalistic incentives, are supposed to bring forth a utopia where all hard problems are solved, everyone is compensated fairly, and no one is ever made to feel unhappy or unwelcome. But they come into a system that’s set up to see them fail. Being an indie project makes it harder not easier to meet these expectations. After all, large swaths of our online world only survive because of large investors. And even assuming a project were willing to ask for their help, large investors would not find the financial return they seek in the projects we need and would then refuse to fund them. And so, as these projects try to fix everything with nothing, eventually one of two things happens: either the people working on the project burn out, killing the project, or a glaring mistake happens which proves to bystanders that the issue was simply that project runners were not up to the task.

Then we do another round around the block: people who’ve had their hearts broken before are even less inclined to support new projects, and a lot of resentment breeds all around. And the spiral continues.

So now that I’ve described this uplifting and encouraging situation, can we stop this?

There are 3 main ways for a project to try to escape this spiral. None of these are mutually exclusive, and they all influence each other to a degree. I had originally included more about each, but it made this talk run long and I want to have some time to answer questions people have sent in. So let me just give a couple thoughts about the first two, and we’ll look at the third one in depth.

First, “do less”. If you set your sights lower, then you can build what you seek while needing less resources. One way to do this is to take open source software that already exists, modify it a bit, rebrand it and offer it to others. For example, an enterprising group of fans could use the open source software behind AO3 to create a new fanfiction archive with a different moderation and tagging policy without having to build a platform from scratch. This has already happened in fandom before: it’s what Dreamwidth did with LiveJournal, and it has given people a stable, independent home away from big platforms for the last 15 years. But since one of the comments we saw earlier was from one of Dreamwidth’s own founders, you can see this route still comes with its own challenges.

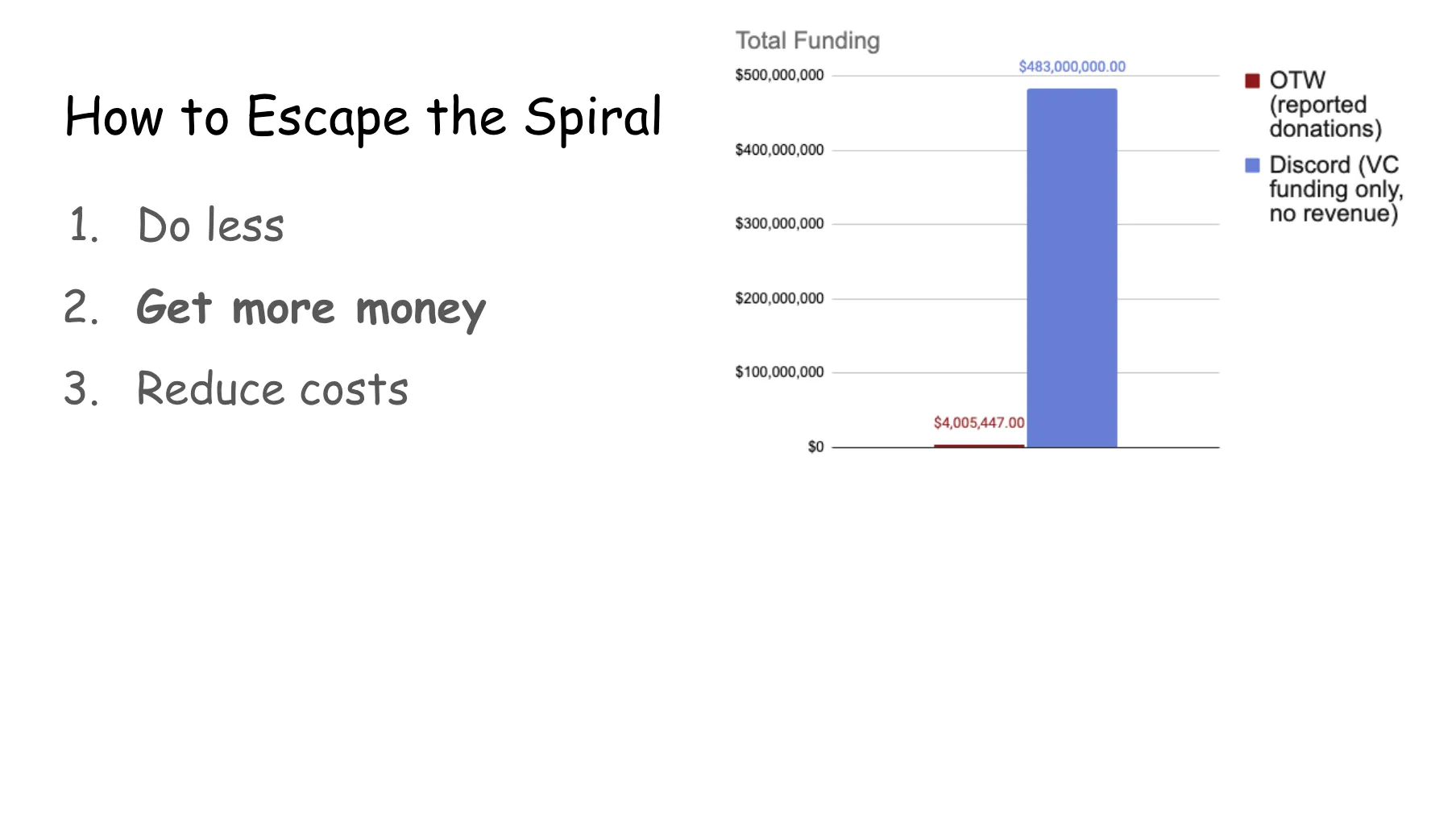

Next, get more money. There is a lot to say here so I’ll just let a picture speak nearly half a billion words…

…cause that is the difference in funds raised by the OTW and Discord throughout the years. While I made this image a couple years ago, not much has changed. Most likely, the disparity has just gotten worse. I want to stress: this chart does not include the money Discord makes selling things like Nitro or getting paid by advertisers for product tie-ins. This is just what external donors invested in the company to buy it enough time to become profitable software, and is what Discord will be asked to pay back with interest one day.

So here’s the last strategy and our focus: reducing costs. There are a few different ways costs can be reduced. Building decentralized software is definitely one, and open source software also helps. But the most tempting option is always the same: volunteer labor. In theory, if you’re looking to build a platform that solves a problem as shared as “better online social spaces” then volunteers seem almost a no-brainer.

After all, isn’t part of the issue that there’s too many of us? And if people feel powerless and in the dark, at the mercy of platforms’ poor decisions, wouldn’t they want to be involved? Here’s where it gets tricky…

…as a famous software engineering maxim says “no matter what the problem is, it’s always a people problem”. Unfortunately, working together with people is hard. BobaBoard, and Dreamwidth, and AO3, along with many others projects did and do indeed recruit the help of volunteers. But as far as I can tell, this alone has rarely been enough to create an environment that is truly sustainable and that doesn’t overwhelmingly rest on a few individuals. And to analyze why that is, we need to talk about power.

Now, this may feel like it’s coming out of left field, but bear with me. Let’s go back to that fateful day when those posts were published. After seeing other project leads talk about the toll of running projects, the frustration me and my collaborators had been feeling spilled over, and we found ourselves discussing our struggles openly within our communities. While the discussion was at times raw, we found that rather than creating fear, uncertainty or resentment and causing people to retreat, it instead renewed a sense of closeness and comradery, with more people coming forward to ask what they could do to help. After those discussions, we did see a vibe-shift in our spaces. Obviously, that didn’t fix all our issues. And yet, why did something change? For a while, my answers were fairly simplistic. It wasn’t until I read about other groups having similar experiences that I got to better understand the role power played.

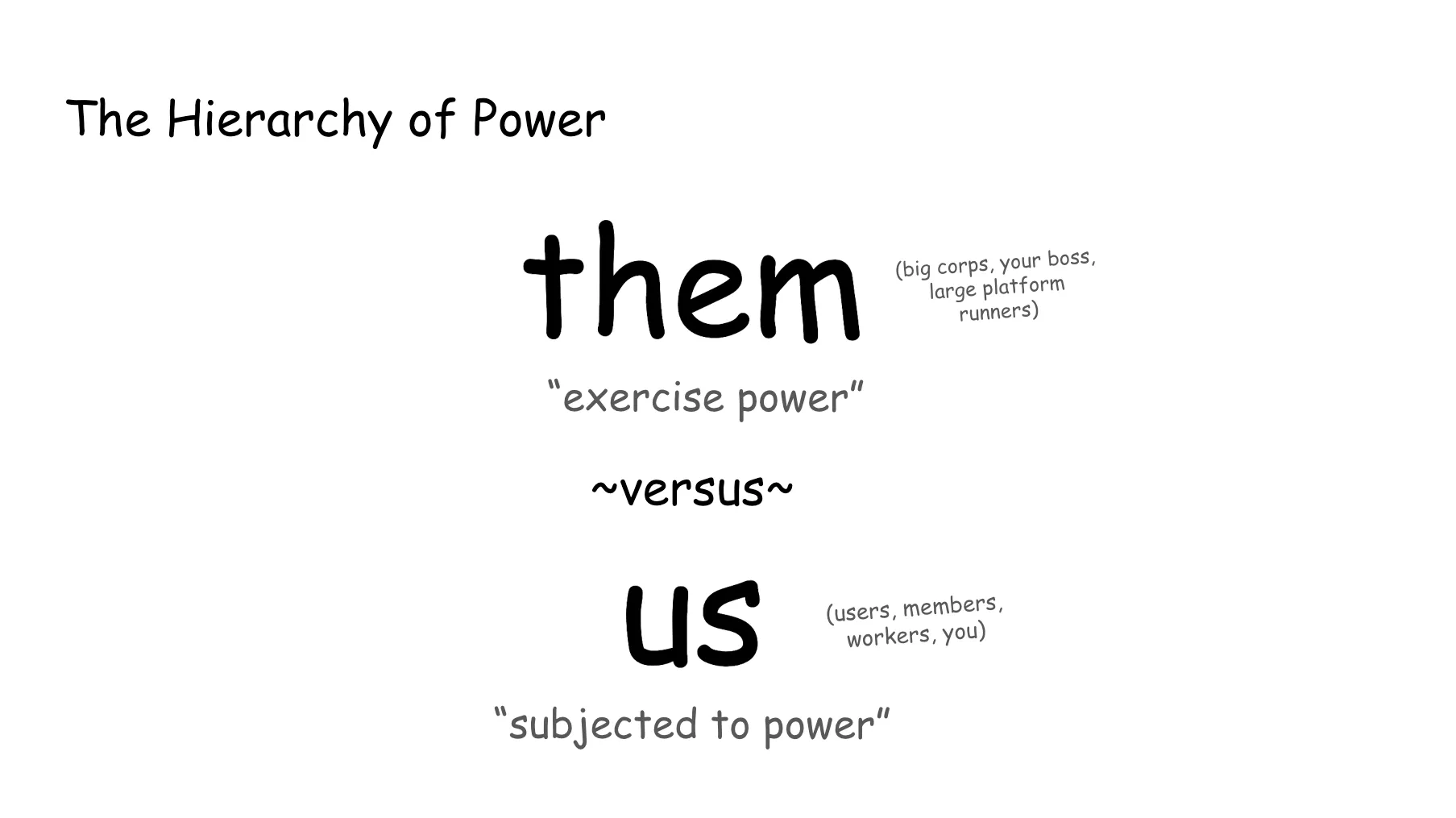

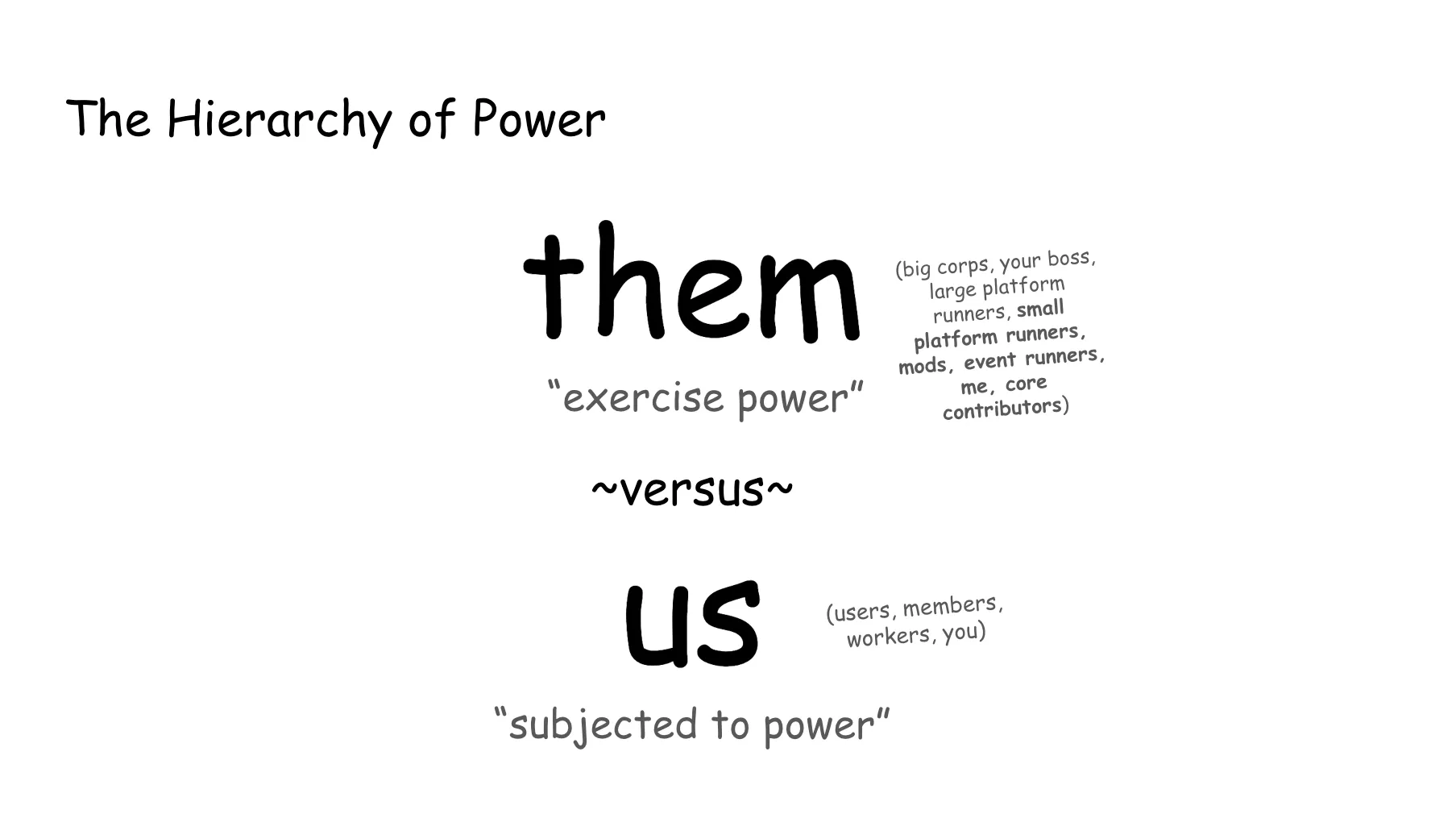

Now, the world as it has existed for a long time overwhelmingly rests on hierarchical power structures. This means we often tend to perceive our relationship with the world as an “us” and a “them”, two separate entities, one above and one below, one with power and one subjected to it. Unfortunately this is so ingrained inside and outside us, as to be inescapable. So when you have people like us small platform runners (but not only) that aren’t quite as powerful as those often slotted in this “them” group, but that still do have some power, where do we go? You may think, “well, it depends on the person”. And that’s true! Power is not an absolute thing, power only exists in the context of a relationship.

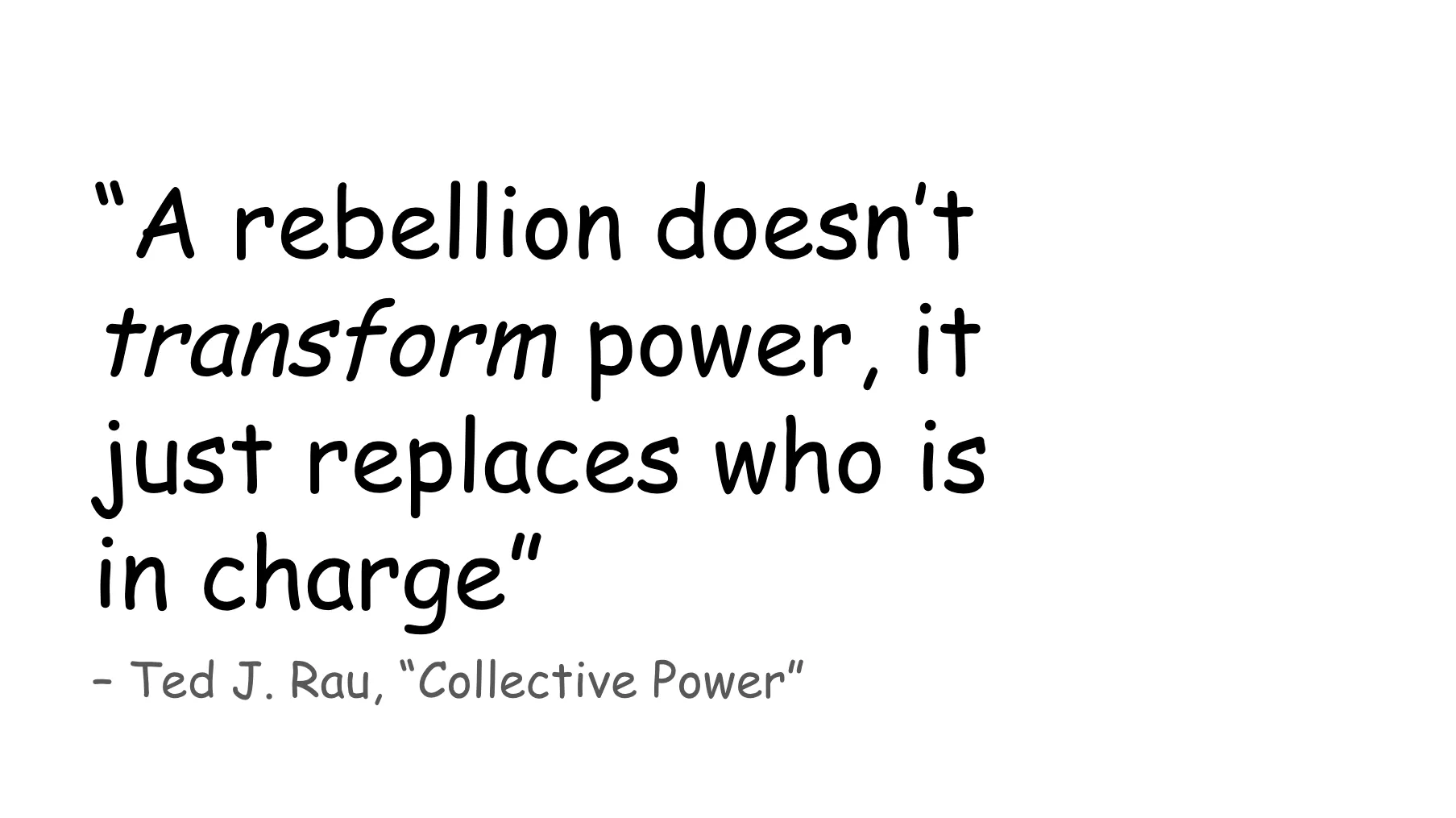

Now here’s the thing: indie projects are often born as a rebellion against large tech platforms, with the desire to shift the balance of power and put it closer to the users. But shifting who is in power doesn’t change that a hierarchy exists, no matter what intentions the power shift is born with. Groups like ours that are overwhelmingly full of queer, disabled, poor, and otherwise marginalized individuals, have often been betrayed and mistreated by those in power. Because of this we’ve justifiably learned to be suspicious of anyone who has it or seeks it. At the same time, we’ve so often been stripped of our own power and agency, that we may perceive those who wield it as fundamentally different.

Because of this, small platform runners can end up in the “them” group (often subconsciously), even for the people we’re here to serve and help. This is not true for everyone, nor it is a fixed thing. I’ve seen this happen first hand: what is a often long-time peer relationship, even a friendship (in a way an “us”) can suddenly take an “us vs them” feel the moment I find myself having to step into a role that has power. Eventually as long as someone is in power, the us versus them is still there. Where there’s power people will either passively submit, leaving all the responsibility in the hands of “leaders”, or actively rebel, antagonizing those above them.

However, when people saw us come forward with our frustration and pain, and express the overwhelming weight of what we were carrying, it made it harder to continue the narrative of us vs them, platform user vs builder, server members vs moderators, person who can’t and person who can. After that discussion people saw us for who we truly are: members of their same community that, for all their weaknesses and faults, are trying to build something that makes a difference. Once people saw the barrier drop, we were able to level the playing field, and it became easier for us to ask for help, and easier for others to give it. It made it easier for people to empathize with us and give us the grace we sometimes need. Now if you’re jumping in your seat going “I know how to fix this! I know how to fix this! Let’s get rid of hierarchy and power”, don’t worry: we’ll get there. But before we do, let’s talk about different types of power.

They say knowledge is power, and indeed one of the most powerful things we can do is to know more about it. So… We all deal with power in our lives but we tend to have an oversimplified view in which it exists as a single entity. In reality, power takes many different forms.

We’re all familiar with power-over. This is the classic type of power that flows from above to below: often wielded through fear, shaming and bullying, where people who use it are more concerned about being right than getting it right. It centers those at the top and disregards those at the bottom. When someone has power-over they can make a decision that affects someone when the decision is not theirs to make.

Power-over is often confused with authority, which is when someone with special context, expertise or insight has earned their position through experience and learning. The opinion of an authority may have more weight not because of their place in the hierarchy but because of their understanding of the situation. But this is only true in some contexts, and it can easily become power-over if authority exceeds its bounds. Now, while we’re used to hearing about these types of power, we’re less familiar with others. In particular, there is one lesser-known type of power I believe is fundamental to understanding the dynamic in our spaces: power-under.

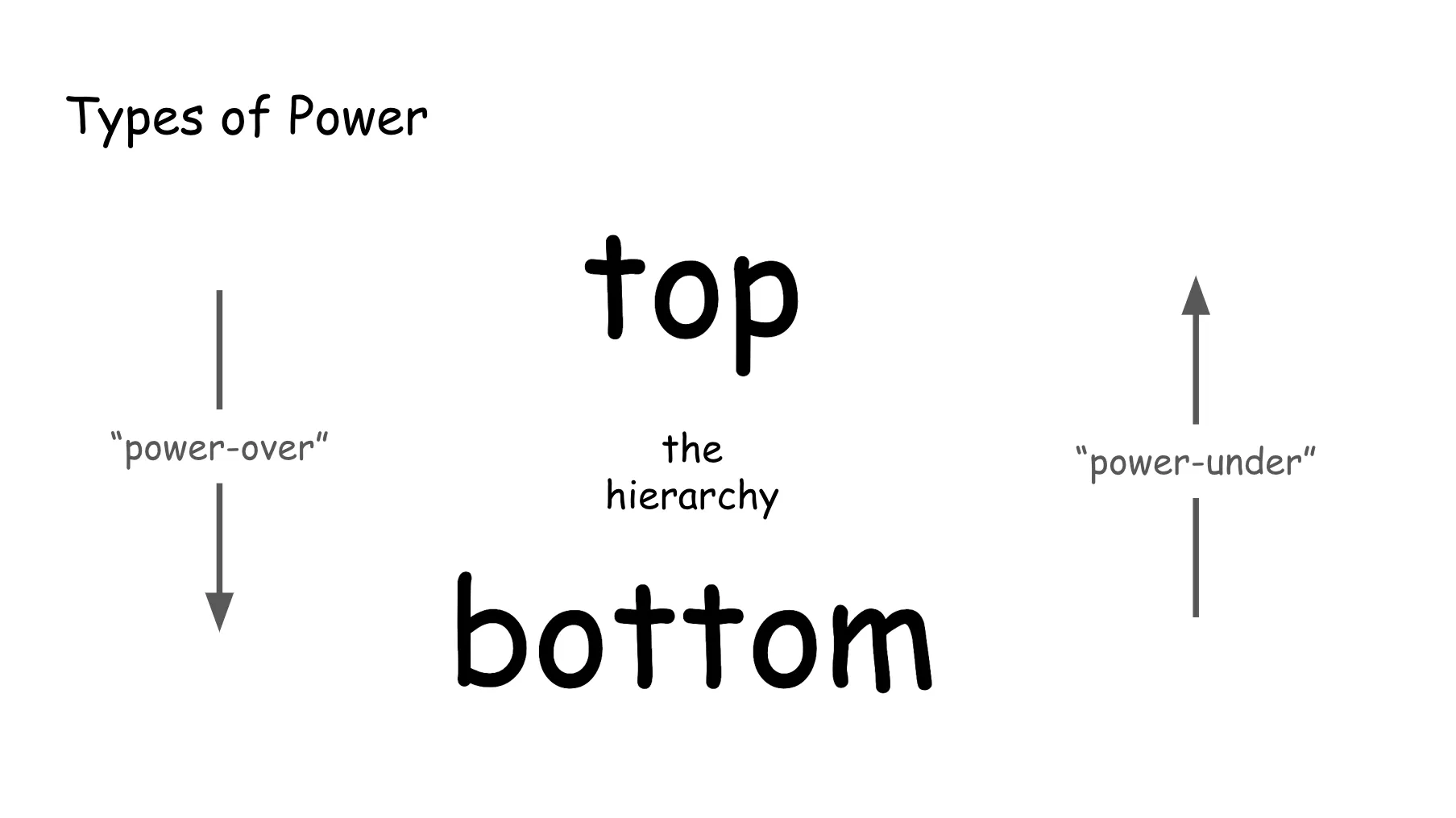

Power-under is power that flows in the opposite direction: where people at the bottom of a hierarchy wilfully avoid stepping into the power that they do have. Now since we often see power as inherently desirable, you may be confused by the idea of choosing to renounce it. But what we tend to forget is that with great power comes great responsibility, and responsibility can be incredibly uncomfortable.

When we renounce our responsibility and let others make decisions for us, we always retain the ability to blame them when they turn out to be wrong, when they were faced with impossible choices, or simply when we don’t like the outcome of what was decided. When we don’t take on responsibility ourselves, we can always say “I told you so” and believe we would have known what to do and done it better. By giving away their power, people also overpower others at the same time.

To show a neutral example, here’s quotes (presented with permission) from a Pillowfort thread I did not participate in myself. You can see people do recognize power-under, even if they can’t name it. And you can see how damaging it can be to small teams of folks trying to make a difference. During rehearsals, I was asked to pause here to let people reflect. So let me drink a glass of water again. — BREAK — Now I want to be clear: just because someone is in a top or bottom position, this does not mean that they exercise these powers, do so all the time, or do so willingly. And power-under does not imply that people use it because they’re evil. Instead, it’s been most often observed as a trauma-response, especially in marginalized populations that may not often have access to “power-over”. So given what we know about the demographics that form our groups, you can see why it’s important that we discuss it and learn to recognize it. Once you know about power-under, you can see it permeate not only our platforms, but our discord servers, fandom events, social movements and so on… and while you can see it morphing and getting worse over time as the web degrades, you can see it has been in our spaces way before this decline started.

DO NOT READ: In this thread, a lot of different hypotheses are brought forward: the lack of agency on social platforms in our current web; the lack of understanding of the reality of running spaces and platforms, not to mention businesses; and just in general the shift of tone we’ve seen, and the necessity to find someone to blame for the suffering we’re all going through. All of these are valid reasons and they do help explain some of what we’re seeing. But power-under [something something this actually has been known to sink social movement for changes and it’s something we all need to be aware of and learn to callout and deal with]

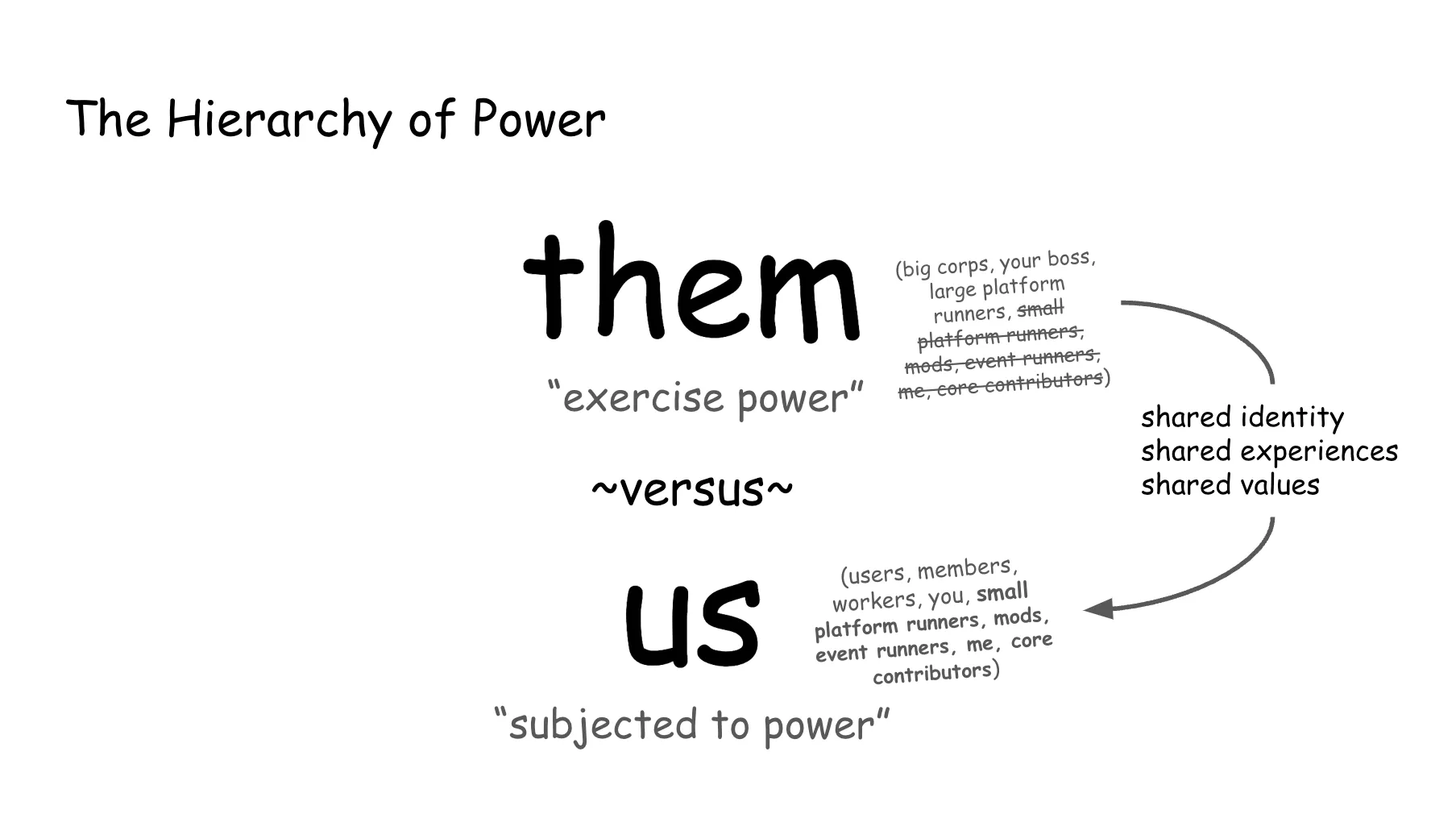

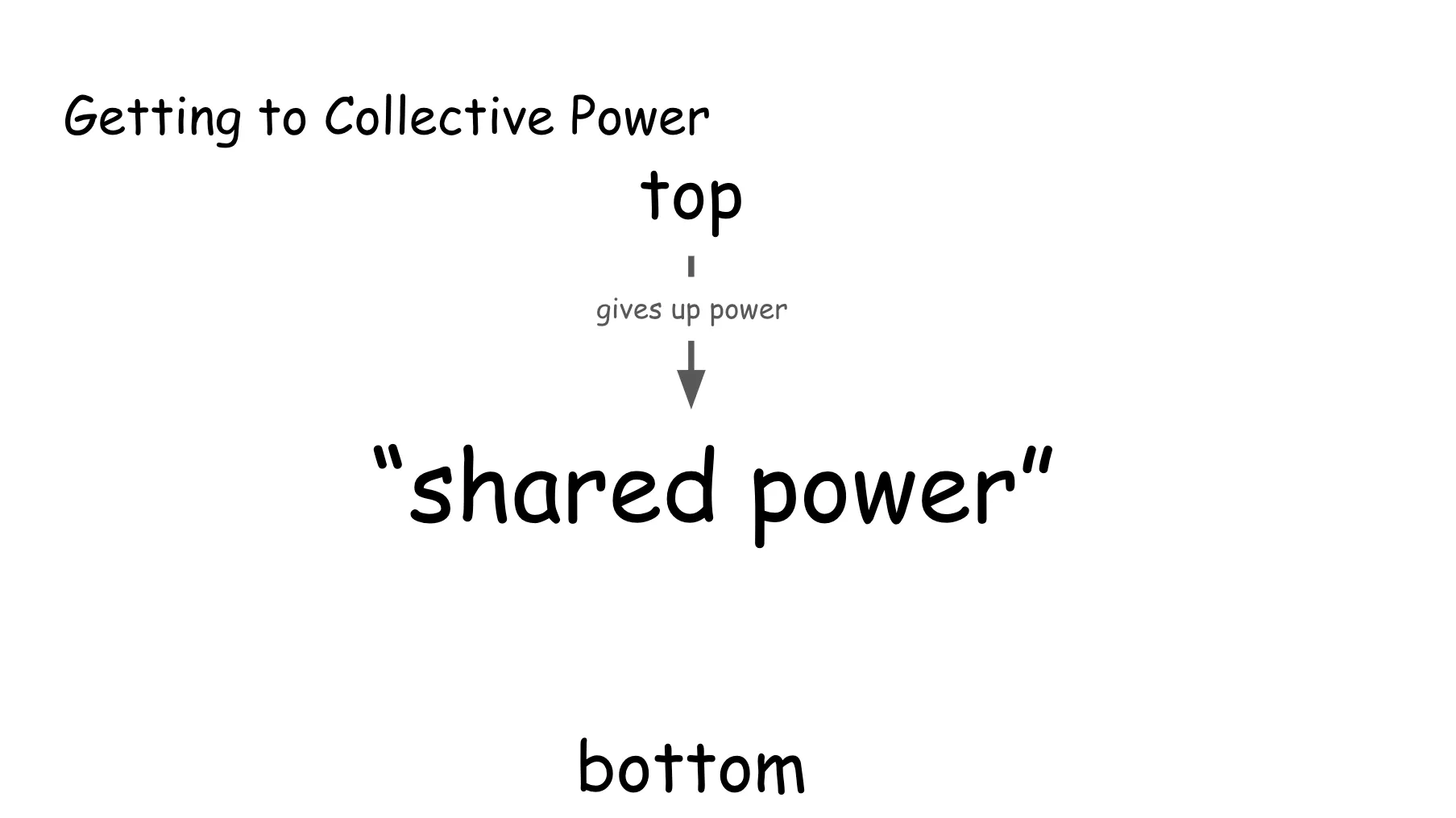

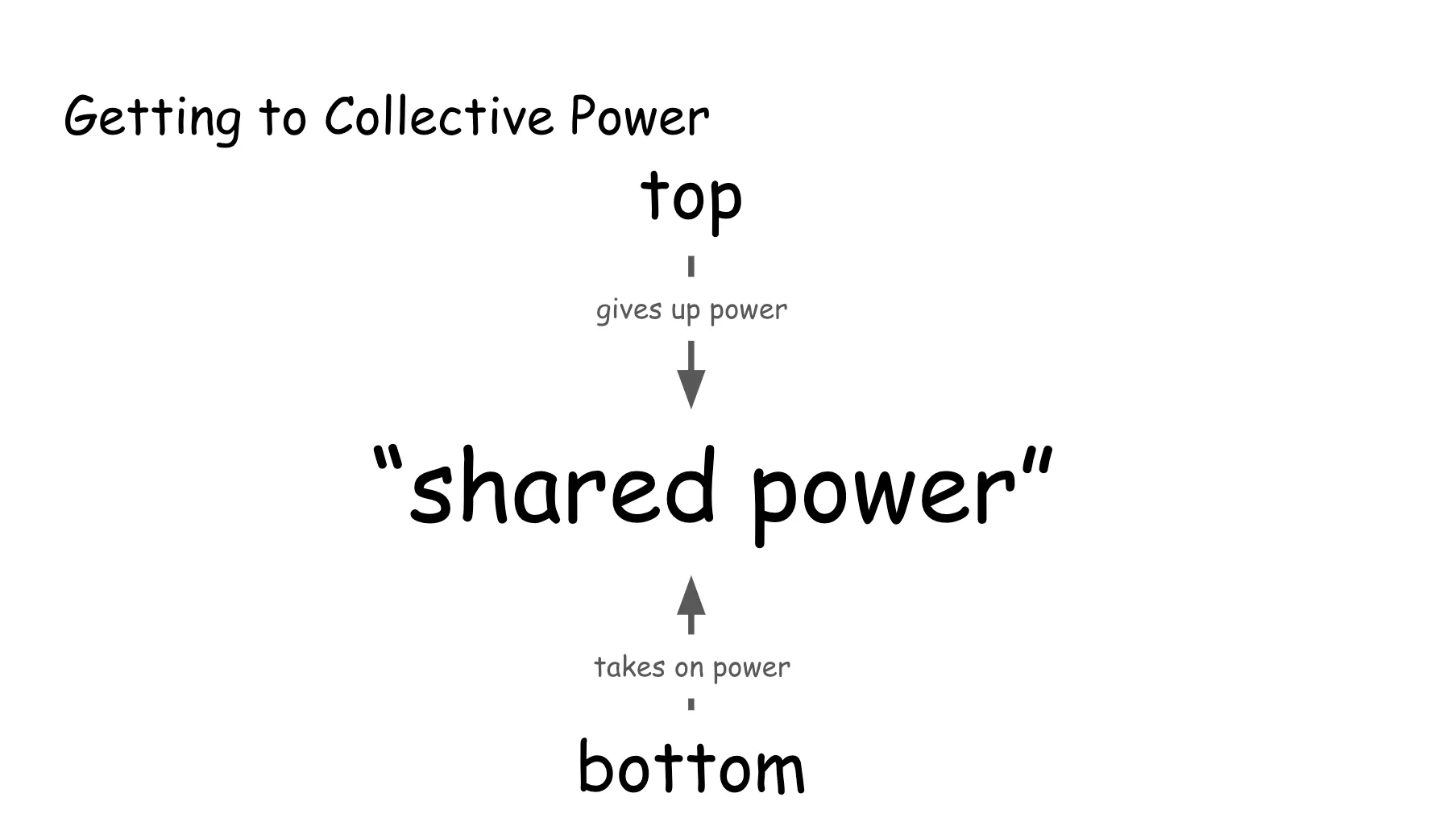

Now that you know this, you can see removing hierarchy is not as simple as having those at the top give up power. To get equal power, those in power do need to step down…

…but at the same time those with less power need to step up: collective power, power shared between platform users and builders, can only happen when everyone uses the power they have.

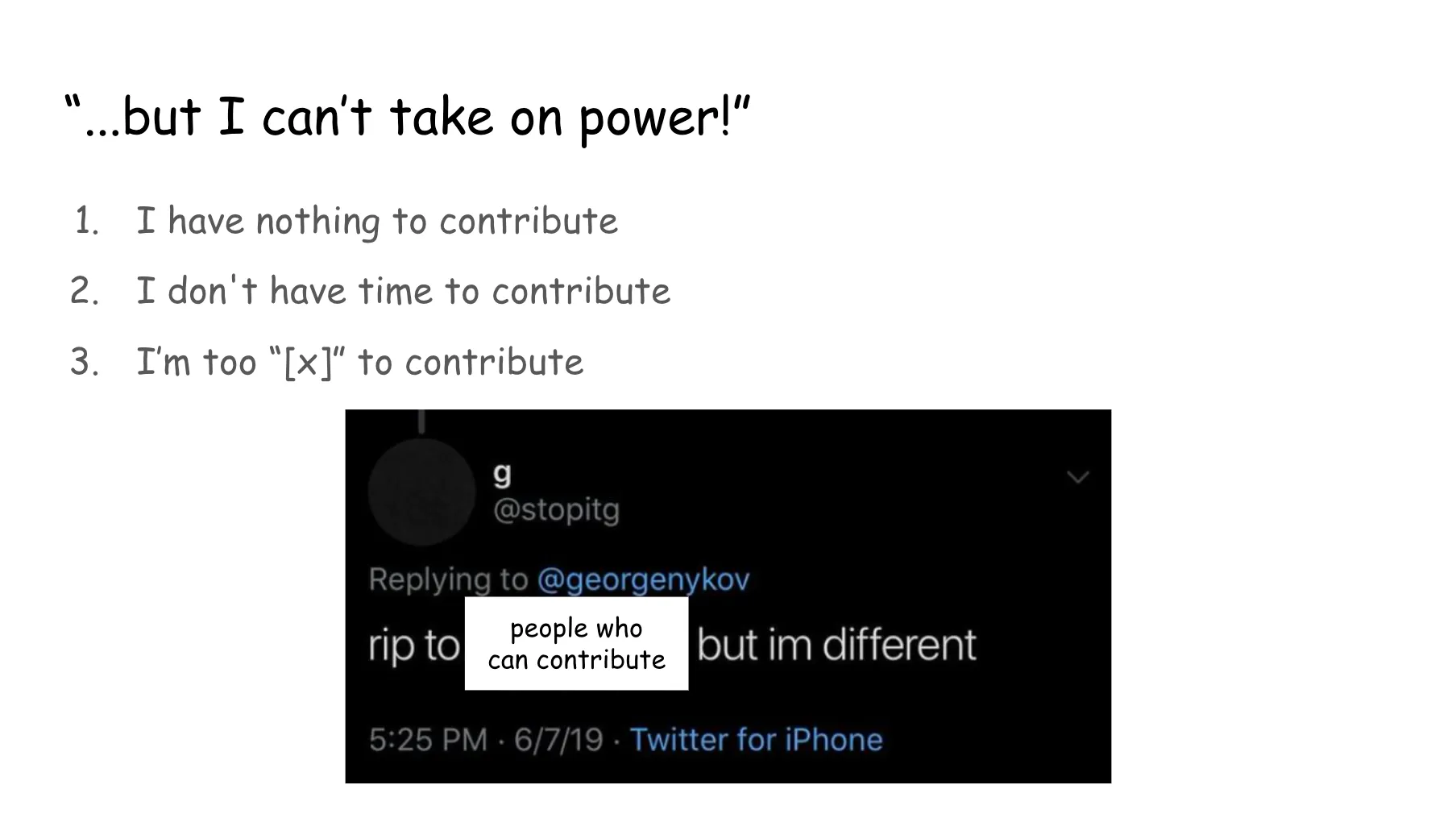

Now, I’ve been around these spaces long enough to know what some of you are thinking: well, this sounds great for people who do have power inside them, but this surely does not apply to me! I don’t have anything of value to contribute, and my personal life circumstances would keep me from participating anyway.

This goes back to something I said before: for many different reasons, people sometimes see those of us working on these projects as inherently different. And when we discuss these differences, these are the points we most often see come up. Before we go forward, an important reminder: it is not up to me to decide whether you can contribute or not. Nothing I say should be taken as implying anyone is making excuses. Your power or lack of it is for you to self-determine. But I do believe it’s important for me to publicly spend some time talking through each one of these points, as my collaborators and I did privately after the Fateful Day™.

So, let’s go in order!

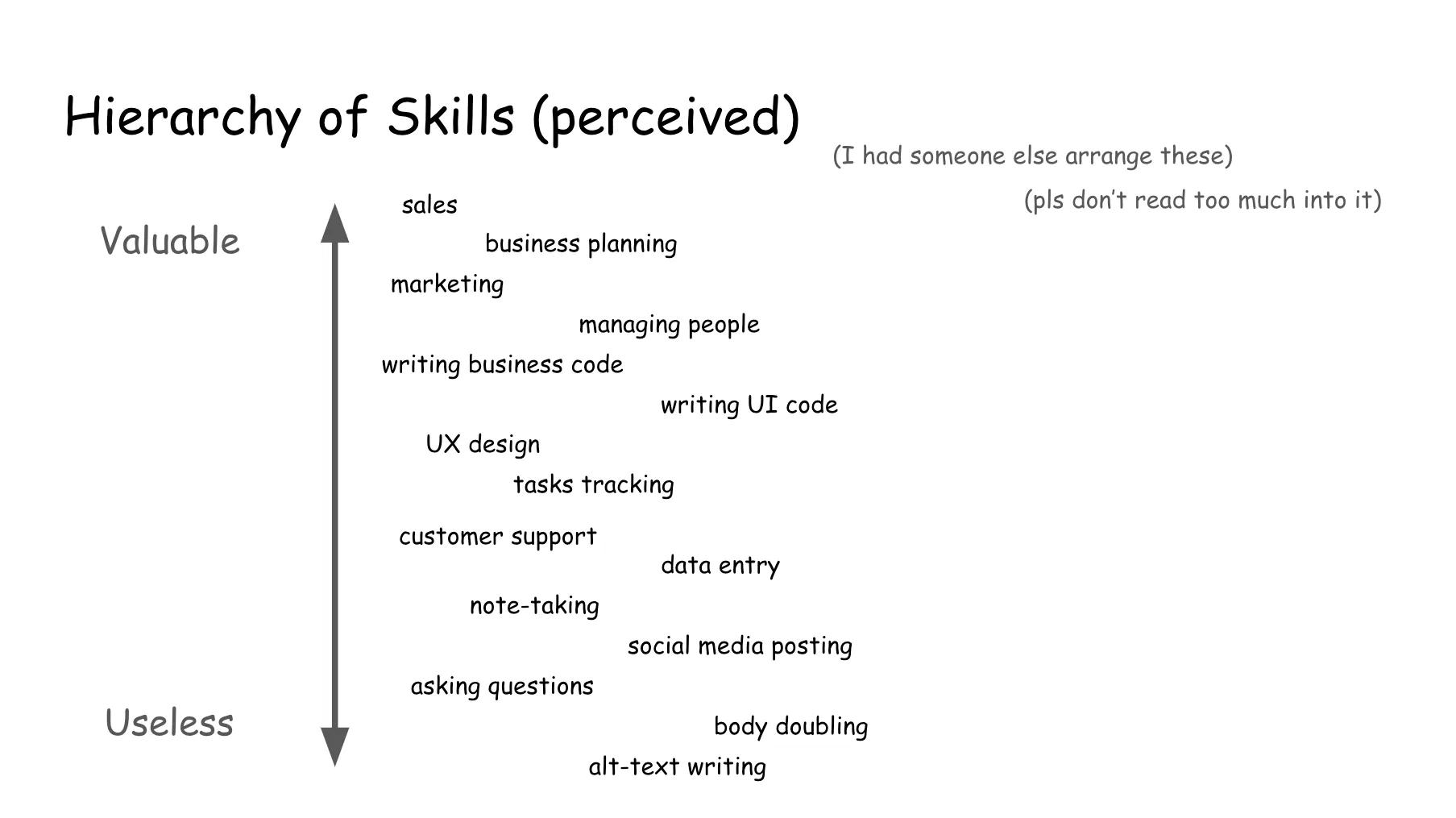

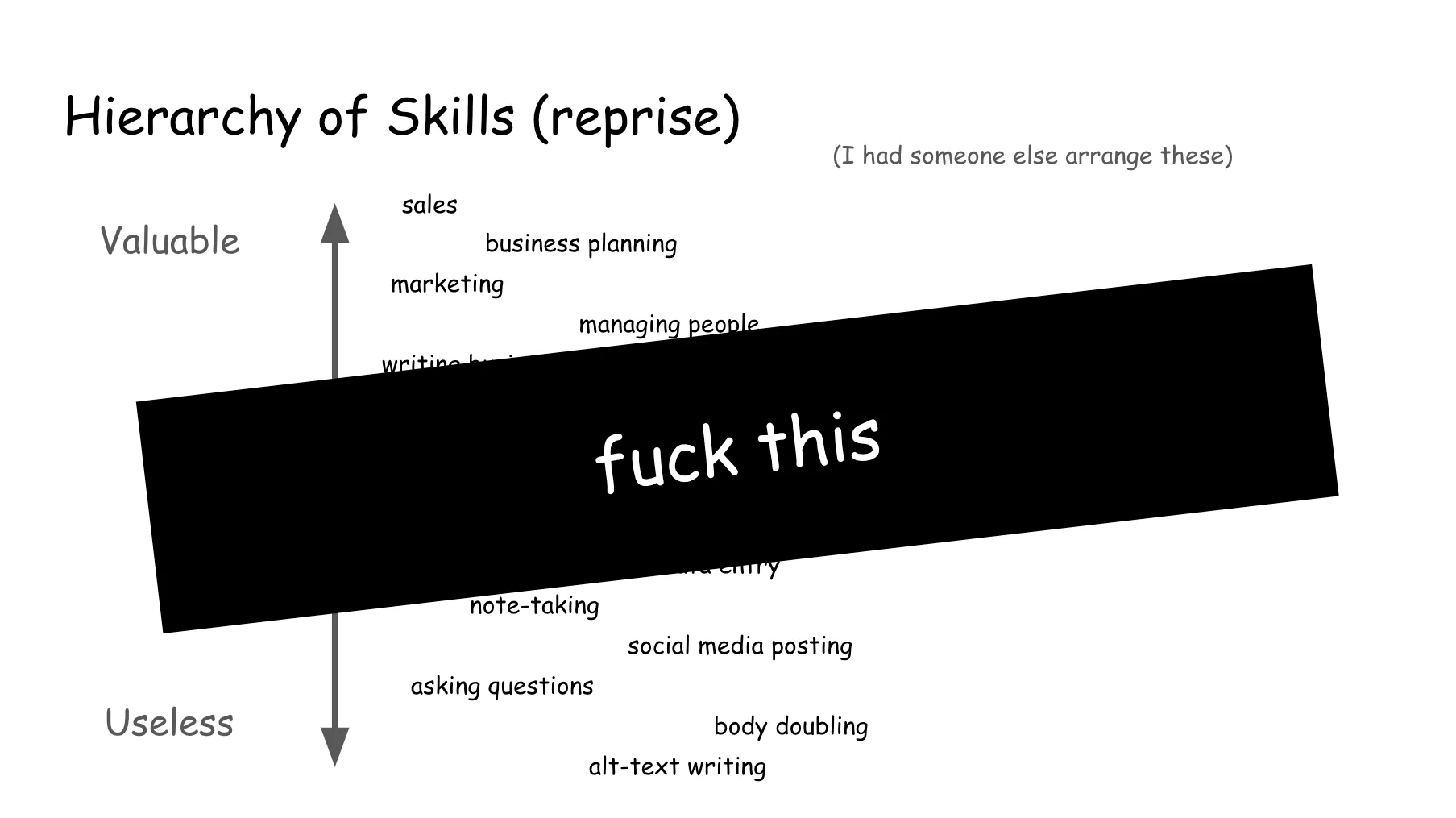

When we talk with people about what hesitations they have about joining our project, we often hear the same answer: “I don’t have any valuable skill to bring in, and all I’d do is bring everyone down”. Now, here’s the thing: when we think about hierarchy, we see there is not just a hierarchy of power in our society, but also a hierarchy of skills. Some skills are seen as more valuable than others, which are instead diminished and dismissed. Since we tend to see skills as a fixed thing you either have or don’t have, this means that if there are valuable and useless skills, there also have to be valuable and useless people. But not only is that not true, that wildly misunderstands how skills are built and the type of skills a group needs to succeed.

Let’s take me as an example: there are some things I’m naturally good at. These include things like “software engineering”, “abstract math”, and “shitposting”. And I was lucky enough to be born in a era where my natural aptitude for computers made it possible for me to be regarded as a “highly-skilled professional”.

However, there’s also things I’m naturally terrible at, that I’ve only become (relatively) able to do through active learning or repeated practice. These include things like “business”, “marketing”, and “community building”.

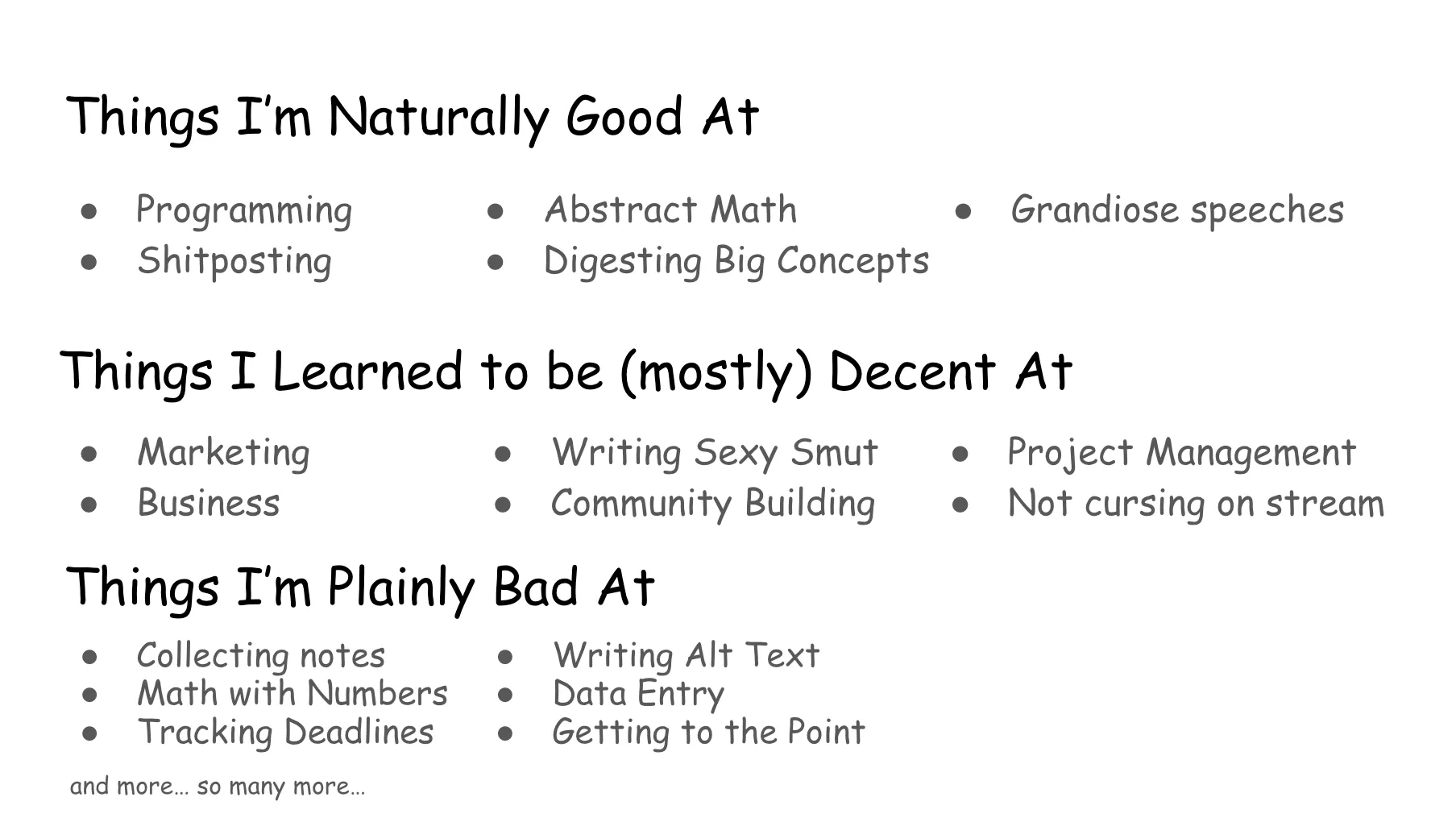

And then there are things that I never have been able to practice, or that I still suck at despite trying and trying to get better at them. There are also things that, while I’m theoretically able to do well, take a disproportionate toll on me and quickly sap all my time and energy. These include “collecting notes after discussions”, “assigning people tasks”, and “entering data”. Because of my position as one of the “doers” and because some of my natural skills are so high in the perceived hierarchy, I’ve found that people tend to assume that if I possess the skills at the top, then I must also inevitably possess those at the bottom. That couldn’t be further from the truth. Very often when I talk to people about the skills I lack and what I’m desperately struggling with, I see a light bulb go off above their head: “oh, that’s not hard at all”, they say, “I love doing that type of task”, or (one of my favorite to hear) “I didn’t even realize that was a skill”.

So allow me my one swearword in this PG-13 talk: fuck the hierarchy of skills. To build successful projects we need many different types of abilities, all across that “so called” hierarchy. Just like we’d be unlikely to succeed without someone who knows software programming or without a good business plan, we’d also have a hard time going anywhere without the skills society tries to convince us are useless. Some of the most impactful and positive contributions to our project have come from people who collected data, updated our socials, asked questions, and wrote alt-text for our posts and websites.

Now, the second one: “I don’t have time”. This is completely understandable! Time (and mental space) are incredibly limited nowadays. But just like we tend to think we need to have big skills to contribute, we also think that we need to do things that take a lot of time. And yet, there is something anyone running or joining projects needs that requires very little time to do…

…and that is actively showing your support!

One of the hardest things any creator and platform runner deals with is complete silence. There’s nothing more alienating than doing things for an unresponsive audience, and not hear back until something needs fixing or changing.

Whether it is personally thanking someone who’s doing something in your spaces, gushing about their work with others, or boosting their posts on socials, interacting with people working to make your communities better is guaranteed to make their day, and doesn’t take much time.

Now you may think: but that’s so little! And, well, to be blunt it is! But this is where we’re currently at. I’ve heard this over and over from many sources: people who are doing essential work for the health of our fandom web and communities are struggling to get back even a simple “thank you”.

And if you want to do more start looking carefully at your spaces: you’ll soon notice small bits of work people may use help with that no one else is taking up. Here’s some examples I was given of requests that often go unheard: helping to choose the day an event should be held on and create a calendar invite, submitting ideas for a “question of the day”, saying hello to new members joining a Discord server, or helping fill entries in a community wiki. You may not be the perfect person to help with any of these, and yet you may be the only one doing so!

And now the hard one…

This is something that’s very hard to talk about, and I wish I had had more time to have many people review my wording and be confident I’m conveying the right amount of nuance with the perfect phrasing. Unfortunately, this talk took way too long to prepare, and the time for this topic is shorter than ideal. Remember I speak as an inside ambassador: some of our most important collaborators have disabilities that significantly impact their lives; some of our collaborators have had significant life and health events; a lot of our collaborators struggle with mental health, to the point that we have (as someone defined it) “a bingo-card of mental illnesses” among our team; and obviously some of our collaborators are poor, overworked, and in generally difficult life situations. When those of us who face these struggles have talked about contributing with people in similar situations, we’ve repeatedly encountered something we believe needs to be talked about.

And that is learned helplessness. Here’s what this may look like: Maybe we fail to meet a deadline for reasons we even struggle to explain, and feel the weight of the other person’s disappointment, or worse we get yelled at. So we stop showing up for tasks with deadlines. Or maybe we see someone effortlessly breeze through tasks we don’t even know how to start with, and when we struggle with the same we get the task taken away, or worse get mocked for our inability to complete it. So we stop showing up for tasks that are hard. Maybe we’re told people like us will always struggle, so we come to believe that we will never amount to anything. The trauma of learned helplessness builds up slowly, over time. Eventually, we stop believing we could ever meaningfully contribute to our projects and our communities. While everyone’s life circumstances are different, I’m here to tell you: it may come with unique challenges, it may not be easy, you might need support and encouragement and a safe space to fail, learn, and get up to try again, but all of us have the power to show up and make a difference.

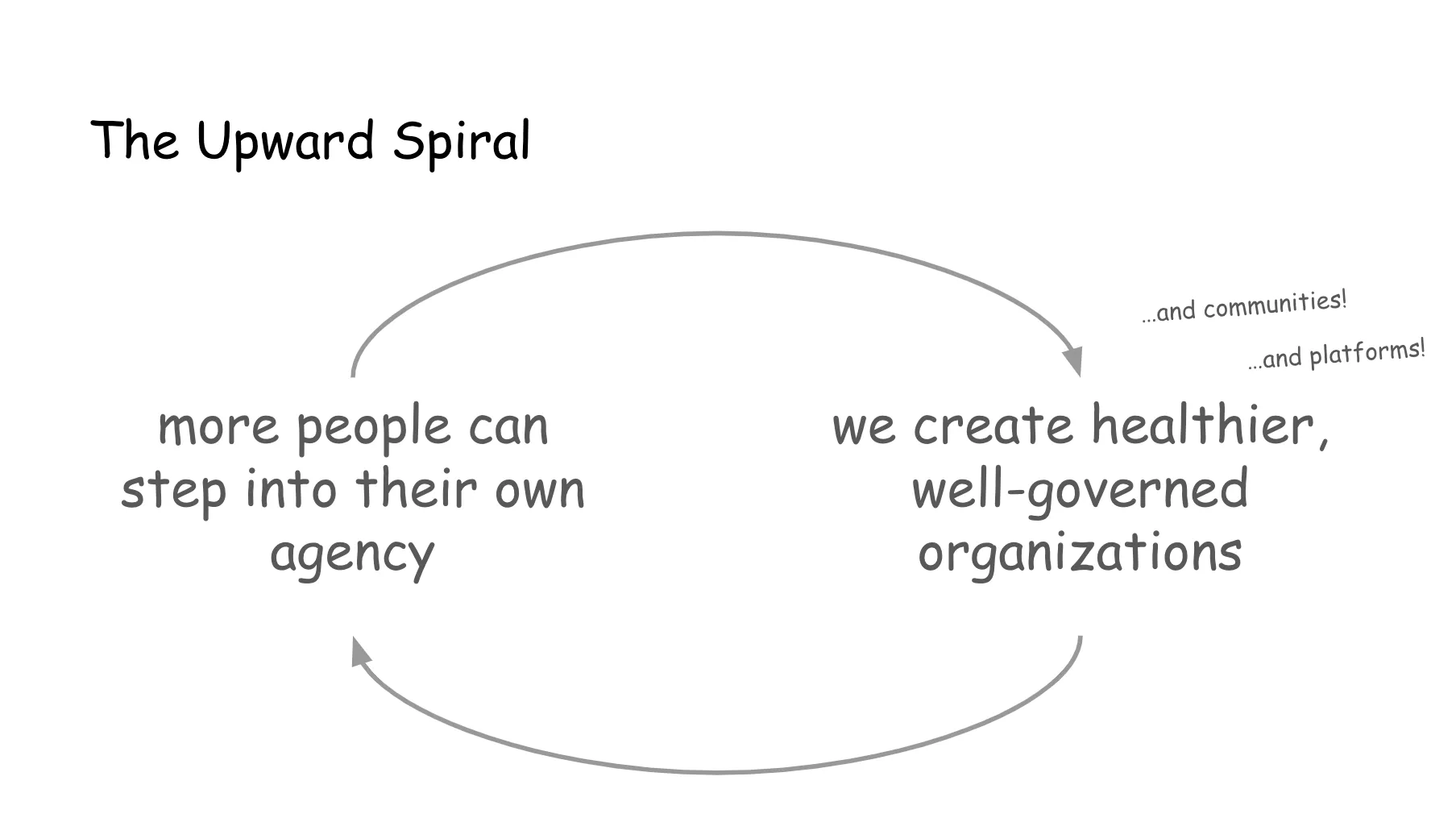

And this brings us to the last type of power of today: power-within. This is what happens when we’re able to step into our own agency, see that we are capable, and believe (or even better know) that we can meaningfully contribute to our collective. During this journey, we’ve met many people struggling with learned helplessness and saw them overcome it to reach power-within. When this happens, people are transformed. They often go from timid and hesitant to eagerly volunteering their skills and opinions. They learn to say, “I don’t know if I can do it, but I will try”. They learn to recognize when a task does not play to their strengths, and see failure as an inevitable condition for growth rather than a personal defeat. Even more importantly they go from needing encouragement, to giving encouragement.

Helping people step into their power is hard work, and not everyone can do so within organizations as messy as the ones that exist today. But that makes it even more important that those who can show up for this stage of the journey help us create an upward spiral that counters the cycle of hopelessness we’re currently stuck in. More than any piece of software this is what will rebuild our communities. Because real community happens when people help each other become who they want to be; when people come together to share information, skills, hard-won lessons, attentive care, and above all friendship; and, when in the process of doing so, people create something that is bigger than the sum of their parts.

And with this hopeful message, it’s time for the last big question: is what we discuss today enough? Well, I’m sorry to say that alas, harnessing the power of more helpers is a necessary but insufficient condition to escape the current situation. Here’s the problem:

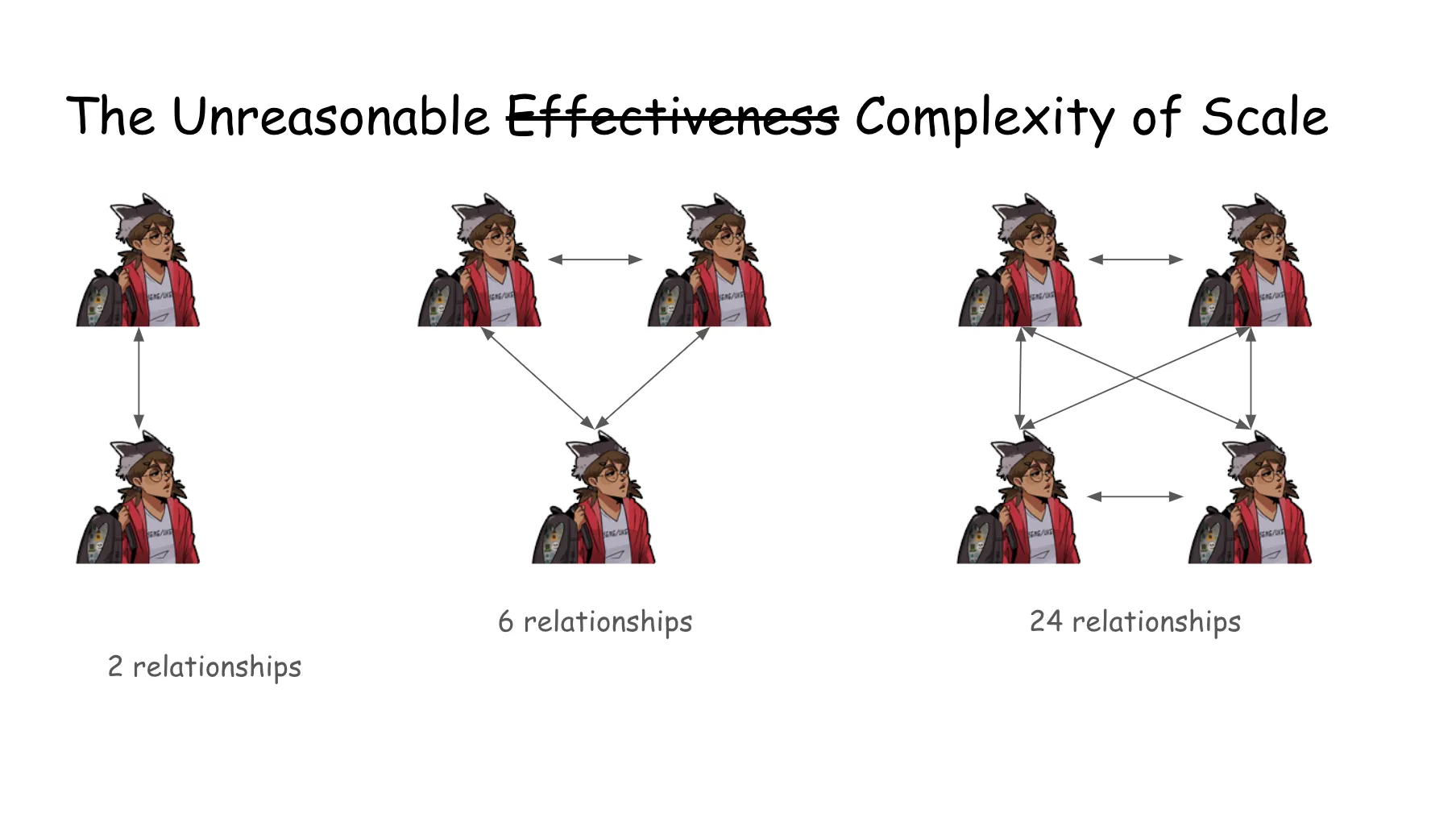

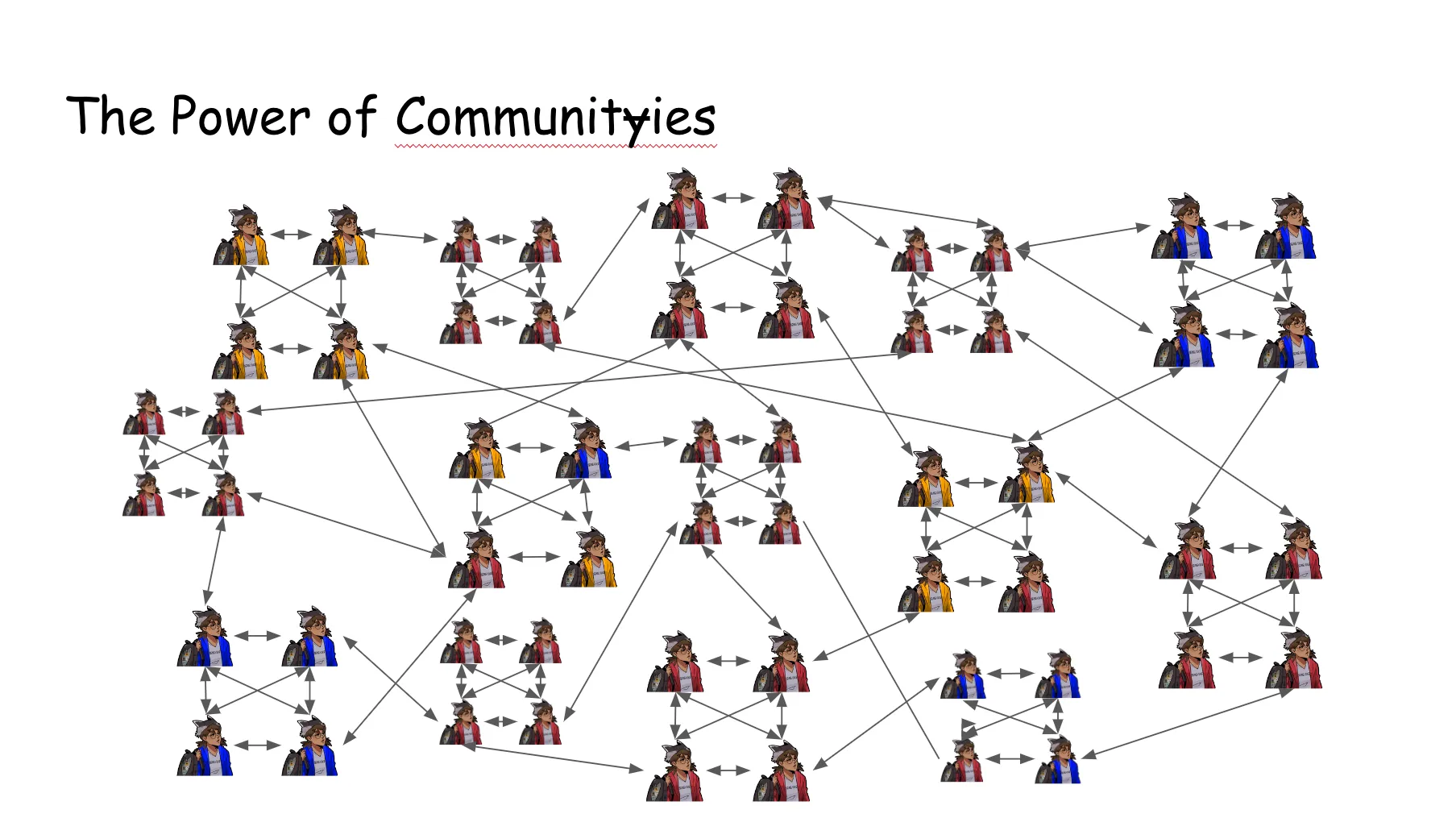

As you know the larger the cast the higher the number of relationships between its members. Similarly, when more than a handful of people come together to work on a project, complexity increases dramatically. Every person adds more arrows to the graph of relationships, and every arrow adds new possibilities for misunderstandings, missed expectations, someone shipping your NOTP, and eventually proper conflict.

Going deep into this would require us to explore trust, psychological safety and self-responsibility. However, this talk is already long, so I’ll leave you with just a few thoughts: as things are now, it’s hard to feel safe and secure in the spaces we inhabit. When we feel under constant threat, it’s hard for people to speak up when needed and to listen when necessary. When the collective suspicion, resentment, and pain that results from their members feeling silenced, disrespected or otherwise unsafe eventually boils over, organizations often clench up in response. They tighten their ranks, become less transparent, and attempt to maintain order through increased control and hierarchy.

But we can create environments where feedback is gladly given and received. We can teach people the skills to solve their own conflicts from a place of love, giving them a true sense of responsibility for the words they use and the environment they create. We can build projects where we collaborate on an even field despite our differences. But creating those spaces starts with understanding that organizations and communities are messy. Being together in harmony is the biggest problem humanity has ever faced, and one we continue to struggle with. Despite what we may think, building good organizations is not a solved problem with an easy blueprint to follow.

But this has started to change in recent years. Within the past year, I learned about sociocracy, a peer governance system that uses a mechanism of circles and consent to enable non-hierarchical, decentralized decision making. A lot of what I discussed today I only learned thanks to the educational material created by Sociocracy for All, an organization that helps other organizations learn about and adopt this system.

I hope today helped you appreciate how the problems that plague our web and our communities are complex and intertwined. No one knows how to fix all of these problems alone, and not all of them even have a clear solution.

But here’s the good news: just like we are not alone as people, we are also not alone as communities. There’s a lot of groups out there solving the many problems on the way to a better, more equitable, more communal online and offline world. I mentioned Sociocracy for all already, but we also wouldn’t be here without the Sustainable Economies Law Center, that has given us free legal advice that helped me go from someone terrified by the american legal system to someone who’s still terrified by the american legal system but that can understand and navigate some of the issues it presents. And obviously I would be remiss not to mention the work that Dreamwidth did paving the way and that they continue to do on both the legal and platform sides, as well as offering us support and advice as needed. Similarly, it’s important to recognize the inspiration that the OTW provided as well as the wisdom its individual members have shared with us.

Eventually true change on a large scale does not happen by working together as a single group, but by empowering people to create new ones and work together on the problems that matter to them, with their unique power and perspective. When such a system exists, everyone can find the place where their power can be put to use in a way that best matches their work style and values. And just as importantly, the failure of one project won’t cause the whole system to collapse, but instead makes us all stronger by teaching us what we didn’t know before.

And with this our talk comes to a close.

In March, some time after “that fateful day”, I officially stepped down as BobaBoard’s project lead. While I’m still involved with the project, this gesture explicitly signaled my decision to renounce the power I had and put BobaBoard’s future in the hands of the community. I’m happy to say people gladly stepped in to take on the power I had given up, and thanks to the hard work of some contributors, we’re now in the process of growing BobaBoard as a sociocratic organization. Progress is slow, the todo list is ever growing, but we’re working hard to remove me as a bottleneck and unwillingly-central decision maker and enable people to come help us make BobaBoard a reality.

And then this April, me and a few other BobaBoard volunteers officially founded FujoCoded LLC, with the explicit goal to empower members of online subcultures to shape their own web and build a kinder, more diverse, more collaborative internet.

The projects we run are many and varied. They range from teaching people how build and collaborate on software by using hot fictional versions of programming languages, to starting communities that help people find support on their coding journey, to building experimental software like BobaBoard that will give them a place to come learn and create their own web.

This new chapter of this story has just started, and there’s no telling where it’ll end up going in the future. Knowing our next steps doesn’t make the journey an easy one. But I’m excited and eager to continue working on nurturing an internet that has meant so much to me, alongside the friends who helped make this journey possible, and the new faces we’ll continue to meet along the way.

And with this, I’m done! Don’t forget to go check out our website to sign up for our newsletter, support us on Patreon so we can continue providing awesome educational resources, and buy our incredibly cute merchandise on our store! Thank you

Footnotes

-

As everything on this page hopefully suggests, you should picture me saying all this in front of a live audience. ↩

-

Once a Cho Hakkai girl, always a Cho Hakkai girl ↩

-

“Exploring your teen queerness on fandom Yahoo groups” is (I believe) just the 00s version of the 10s’ “exploring your teen queerness on fandom Aminos”, which (probably) is now “exploring your teen queerness on fandom Discord servers”.

May it have been as fun and exilarating to you all as it was for me—I’d say “not as dramatic though,” but I know fannish teens. ↩ -

08’s me was sweet and innocent and had drank a lot of sweet-tasting tech kool aid. But, while you’re

hearingreading the story of me discovering things aren’t as bright and rosy as I imagined, I want to stress: being able to move to the USA, undergo the professional development a big tech company will offer, and earn a tech salary did change my life and it did lift me out of poverty. I will forever be grateful to the tech industry for that, my many gripes with it aside. ↩ -

Yes, I survived “Tom Hiddleston takes over Hall H”. AMA. ↩

-

I’m sure this particular executive never thought about their comment again, but every time I think about it whenever I find myself asking “can this category of people really be that out of touch?”. ↩

-

See it from the POV of an average successful Big Tech Executive who goes on Twitter mostly to post some pre-made statement about how proud they are of a launch, or to retweet some company announcement: they don’t know what callout posts are; they’ve never seen a BYF; they live—or did at the time—blessed, simple internet lives. ↩